The poisoning of Hugh Trevanion

Two inquests failed to establish whether this wealthy young man died by suicide or was murdered... but why was a Swansea private detective involved in the case?

Wealthy Hugh Eric Trevanion died at his flat in Grand Avenue Mansions, Hove, Sussex, on 11 September 1912. He was just 27 years old, and left an estate valued at nearly £60,000.

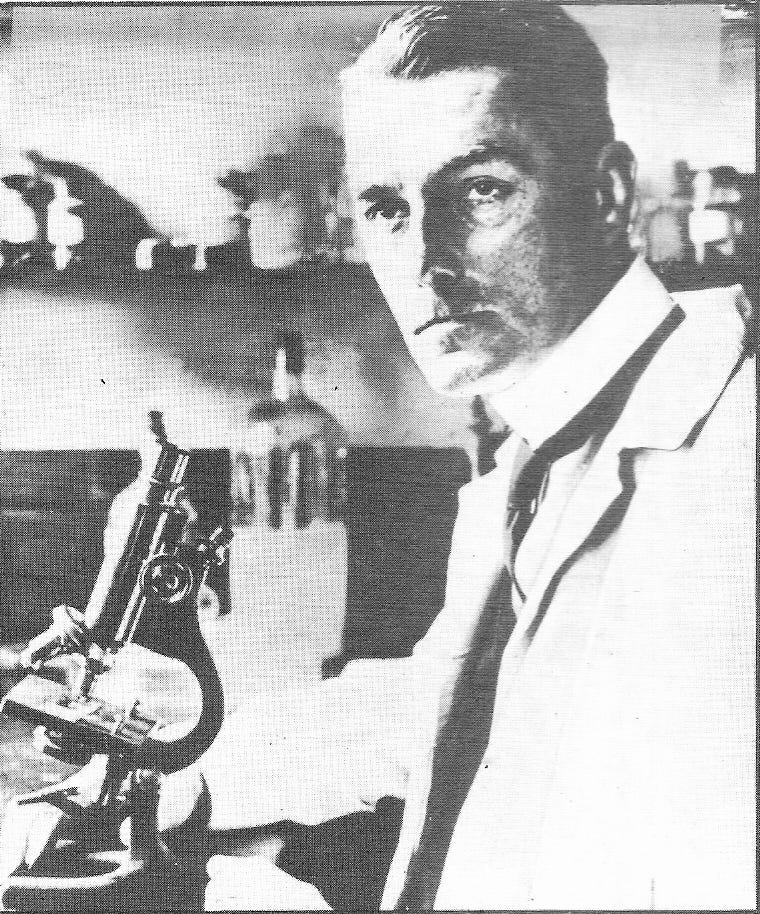

A photo of Hugh Trevanion published in the Weekly Dispatch, 2 February 1913

Hugh had died as a result of being poisoned by veronal - that much was soon evident. But had he taken the poison himself, or had he been poisoned by another party? What was the reason for his untimely death? These matters would be discussed over the next few months, during two separate inquests, and during them, a Swansea private detective would be involved.

The initial verdict into Hugh's death returned a verdict of death by misadventure, but not all the facts had been made public, and the Director of Public Prosecutions instigated a fresh inquest, which was duly ordered by the High Court. This new inquest started on 24 January 1913, a Friday morning, and the interest in the case was clear from the rush of people to get a place in the court. His mother Florence attended the proceedings, accompanied by one of Hugh's brothers.1

Pathologist Bernard Spilsbury, who examined Hugh’s body

Evidence at the first inquest suggested that Hugh had taken veronal to help him sleep; he died early in the morning of 11 September. The coroner had felt that the evidence was so clear, there was little to be gained by conducting a postmortem. Hugh's family, however, was unhappy with the verdict, and made this clear to the Director of Public Prosecutions. The body was duly exhumed on 18 October, and Bernard Spilsbury, the eminent pathologist, examined it and found that Hugh had ingested a massive quantity of the poison - some 150 grains in the hour before he lost consciousness.

The coroner was himself 'astonished' at this, and now wondered how so much poison had come to be in the deceased man's body. The ordinary dose of veronal was between five and ten grains, and Hugh used veronal that came in sachets of around seven to seven and a half grains. This would mean that he had taken around 20 sachets the night of his death, so had he died by suicide, or had someone murdered him?

Trevanion had a history both of taking veronal, and of overdosing on it. His doctor had been called out on both 24 August and 9 September due to this. On the second occasion, he had warned Hugh about this, and Hugh had promised not to take the poison again. However, his doctor had not believed the promise, Hugh having told him that on one occasion he had taken 105 grains, and on another 190. The doctor, Harold Athelstan Barnes, had said he didn't believe either of these boasts, as they were 'absurd'. The Trevanion family's former governess said Hugh had refused to listen to others who warned him about his usage of the poison, and had once boasted, "I have taken enough veronal to kill two people."

It all still seemed fairly clearcut; but doubt hinged on what had happened because shortly before his death, Trevanion had bequeathed a substantial sum of money to a man named Albert Edward Roe. Roe, 35, was, at one point, described as an 'adventurer' who stood to profit from Hugh's death. The two men had originally met in around 1906, when Trevanion, who had weak health, travelled to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The two men subsequently went on many foreign trips together, and Trevanion had expressed a desire for he and Roe to be placed in the same mausoleum when they died, and no other member of the Trevanion family to be buried with him.

One of the many headlines relating to the case - this one from the Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough,

27 January 1913

Trevanion was described at one point as an 'eccentric and, to all accounts, effeminate man' who shared his Hove flat with Roe, and, according to his butler, dressed 'more like...a female than a male'. At home, he wore a kimono with six-inch heels, and was fond of wearing make-up.

It seems clear that he was gay (being referred to in these disparaging terms was clearly designed to hint at his sexuality), and that the two men were in a long-term relationship. Whether Roe - nicknamed 'Bear' by Trevanion - felt the same for Hugh as the latter did for him, however, is not known, but Hugh's family certainly did not want to believe so. This was not helped by Roe admitting that he had told Trevanion that he intended to get married to a woman (name not known, but he said she was around 31 years old) ‘in August’.2

This news sent Hugh into despair. It was widely known among family and friends what the nature of their relationship was, and when asked during the first inquest why Hugh had been so unhappy, his nurse had to write the reason down and give it to the coroner, who refused to give it to the jury as it was 'only hearsay'. Being in love with Roe, who others saw as exhibiting controlling behaviour towards him, and then finding out that Roe was going to get married, were problems that could have made this sensitive young man suicidal.

During the second inquest, in February 1913, previous witnesses were called on again and their evidence challenged. On the last day, the witness was Jack Cranston Campbell, a Swansea jeweller. He had previously given a statement about Trevanion, but had refused to come earlier to give evidence at the inquest. When he finally turned up, he said he hadn't come because his statement was not true - it had been written and signed when he was drunk.

Campbell, who was a lifelong friend of Roe's, then implicated the Swansea private detective Edgar Ford, saying that Ford was in the passage outside the room where Campbell was being asked to sign the statement. It was alleged that Ford had said to Campbell, "Don't sign. Don't go to London. They cannot make you go." The jeweller denied that Ford had said this, and then added that he didn't remember refusing to go to London "to give evidence against a man I have known all my life to get him hanged."

The police, however, insisted Campbell had been sober when he signed the statement implicating Roe, and said Edgar Ford would be able to corroborate their view. However, Ford suddenly refused to do so, or to make any statement. He restricted himself to accompanying Jack Cranston Campbell to the inquest, but refused to do any more than that.

It's not specified in the papers why Edgar Ford was involved; possibly, he had been asked to track down Campbell in order to get him to provide a statement about his friendship with Roe, but why he then told Campbell he didn't need to attend the inquest is not clear. Perhaps he felt that Campbell's evidence might be embarrassing to him personally, and that he should not face questioning in court, or that - as Campbell clearly feared - his evidence suggested that Roe might have murdered Trevanion.

But these were not calls that a private detective should make, and there's clearly more that went on than the press covered. It's more likely that he was simply a friend of Campbell's back in Swansea, and that he came with him to the police station for support. This would explain why he was advising the jeweller what to do, and his later comment, "Don't you say anything, Jack. Don't you sign anything." Given that it seems that Albert Roe was also a native of Swansea, perhaps all three were good friends, and had a vested interest in seeing Roe absolved of any involvement in Hugh’s death.

Ultimately, the second inquest jury decided that Hugh Trevanion had died from an overdose of veronal, but 'how or by whom administered there was no evidence to show' - they had returned an open verdict. As Albert Roe was driven away from the inquest, he was loudly cheered by the waiting crowd, but the verdict meant that nobody would ever really know what happened that night in September 1912.

Florence Eva Trevanion had herself featured in the press four years earlier, when she was granted a judicial separation from Hugh's father, Captain Hugh Arundell Trevanion. The couple had been married since 1882, but Captain Trevanion had committed adultery with another woman. Florence did not want a divorce, but instead sought a separation. Her husband risked prison for contempt of court after he sent Florence anonymous, threatening postcards while the separation suit was being heard at the Divorce Division of the High Court.

An Albert Edward Roe married in Swansea in 1914, and both he and his spouse were the right ages to be the Roe from this case, and the woman he claimed to be engaged to.

This is an amazing narrative. Can’t believe the amounts of poison involved. Thank you for this, just ace.