Blackmailing the Canadian

When Herbert Marshall blew through a financial legacy, he needed more money. His intended blackmail victim, however, was the cleverer man

This week, in the final part of my trilogy of posts about London-based private detective Herbert Marshall, I'm looking at an event from the latter part of his career - one that exposed him as a man who was prepared to act unlawfully in order to make money. For my previous posts on Marshall, see here and here.

Regent Street, London, at the time that Sweeney & Marshall were operated from number 5

While he was working at Sweeney & Marshall, Marshall had employed several other private detectives to help on cases - the workload was too much for just the agency's two proprietors. Two of these men were former police detective Joseph McKenna, who had worked for Henry Slater's famous agency until it folded in the wake of a criminal investigation and subsequent Old Bailey trial (more of this in my next book). Another was Henry Drummond, who had been working for Marshall in a junior capacity since he was 14.

But in 1911, Marshall was working with a man named William Henry Butler. Butler was a former omnibus conductor (as I've mentioned before, private detectives could come from any background, and worked in various careers before taking up sleuthing!). Butler was seen as a slightly shifty character, it seems primarily because of his humble job history. Conversely, Marshall was seen as being of good character, despite his previous escapades both professionally and personally - perhaps because he was a rector's son and regarded as being solidly middle class.

Yet there were clear signs that Marshall was motivated by money. In 1909, he had apparently received a legacy of £2,000, which he had promptly squandered. By 1911, he was in need of money, and, in cahoots with Butler, they hatched a blackmail plan.

Their victim was Elijah Fader, a Canadian who lived on Hereford Road in Acton, west London. The two private detectives stole a number of letters from Fader, and then attempted to blackmail him, accusing him of obtaining an abortion for one Miss Tolley, described as a 'little girl from Manchester'. They said the letters showed that Miss Tolley was threatening to tell Elijah's wife about an affair and the subsequent abortion.

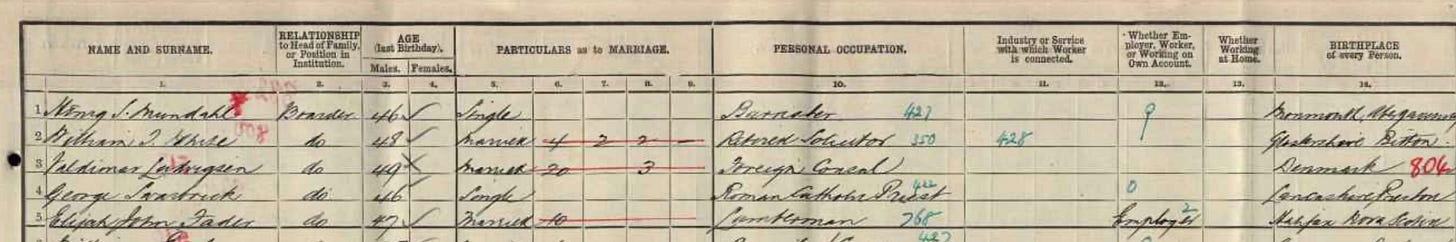

Elijah Fader, listed as a resident of the First Avenue Hotel on High Holborn in the 1911 census, before he moved to accommodation in Acton (TNA/TheGenealogist)

Mr Fader arranged for Marshall and Butler to visit his house one evening to discuss payment of the blackmail. Marshall made clear his aims: "We are going to have some money from you tonight." After a brief discussion, an amount of £45 was agreed. Fader offered to make out a cheque for this amount, but Marshall replied, "We want the ready [money]." Fader then counted out some money, giving them a combination of cash and cheque.

It seemed that the two blackmailers had achieved their aim: but they had not counted on Fader having called the police as soon as he originally received the blackmail demand. As he was negotiating with the men in his front room, two policemen were hiding behind his curtains. When they heard the jingling of coins, and Marshall accepting the money, they came out of hiding. Fader turned to Marshall triumphantly, saying:

"These are detective officers, and I am going to give you into custody for stealing my letters and books from that desk."

As he spoke, he pointed to the desk in the room. Marshall's story about a woman in Manchester obtaining an abortion arranged and paid for by Fader was an outright lie; he knew Fader was married and would not want to risk his reputation for such a scurrilous story, and so had lied in order to blackmail him.

In court, the profession of private detective was critiqued by the judge presiding over the case. He believed that the word 'detective' misled the public into believing men such as Marshall and Butler had a 'previous record for honesty and integrity in the police force'. Marshall never made such claims, but one can see why using the term 'detective' might confuse some people.

In November 1911, both men were convicted of robbery and blackmail. Marshall was sentenced to three years' penal servitude, and Butler to nine months' imprisonment with hard labour.

This was not the end of Marshall's woes. Less than two years later, he faced the Bankruptcy Court, with debts of over £7,000. He blamed his financial woes on 'accommodation bills and being guarantor for undertakings for the benefit of Major St Aubyn'. It is not known what these undertakings were, but he did not mention his imprisonment. It is clear, though, that being a convicted robber and blackmailer would have done little for his career, and a spell in prison was time where he could not earn money. His desperation for money had been taken a step too far, and it looks like it was the end for him as a serious player in the private detective world. The 1921 census recorded Herbert as an unemployed commercial traveller.