The detective burglar

One private detective was asked to investigate a burglary that he himself had committed...

Not all private detectives were honest or law-abiding - as newspapers from the 19th and early 20th centuries show. There was some negativity towards these enquiry agents, partly because anyone could become one. Men and women from all walks of life could set up in business, or claim to be a detective, and for every individual who was meticulous, scrupulous and professional, there was one who was in it for what he or she could get.

I’ve found several detectives charged with offences, with most were charged in relation to their professional work. Perhaps they had gone too far with trying to find evidence of misdeeds, and had faked it in the end, or they had trespassed into a property, or even broken in in order to find documents or evidence of adulterous liaisons. Some, though, went that bit further, using a pseudonym (part of the private detective’s core kit of skills and deeds) and their status in order to claim free hotel accommodation or meals from business owners - they would claim that they were currently working undercover and needed a room, and some hotel owners were so impressed by having a sleuth operating on their property that they would give them a room gratis.

In the case of Joseph Machin Hirst, it’s not clear whether he committed burglaries as part of his investigative work, or whether being a private detective was a cover for his criminal activities.

Born in Lincoln in 1878, Joseph spent his childhood in Peterborough, where he lived with his mother Elizabeth and his siblings. Elizabeth said she was married, rather than widowed, but there is no sign of a husband in either the 1881 or 1891 censuses.

In 1901, Joseph, now 23, was working as a clothier’s manager and visiting the Chapman family in Wandsworth, south London. He then found work as a private detective for a major London detective agency, but by 1904, was working for himself. Joseph had moved from Wandsworth to Balham, and the local area had been seeing a spate of house burglaries. The police had been unable to catch the perpetrator(s) and when one burglary occurred, the homeowner - despairing of the police finding out who had done it - employed Joseph Machin to investigate and try to recover the stolen property.

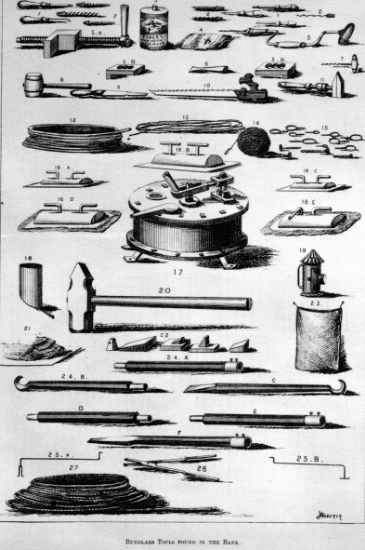

Unfortunately for the homeowner, it turned out that it was Machin himself who had committed the burglary, along with several others. Eventually, one Sergeant Fripp1 realised who the burglar was, and apprehended Machin. His home at Ramsden Road was found to contain equipment that could be used for either private detection or burglary, including 40 skeleton keys, three electric torches, and a police whistle. There were also wire appliances that could be pushed through letterboxes in order to release door catches.

Alongside this equipment, the police discovered victims’ chequebooks and money, together with other stolen property. The private detective had gone undetected as a burglar for some time - but now, he had been found out.

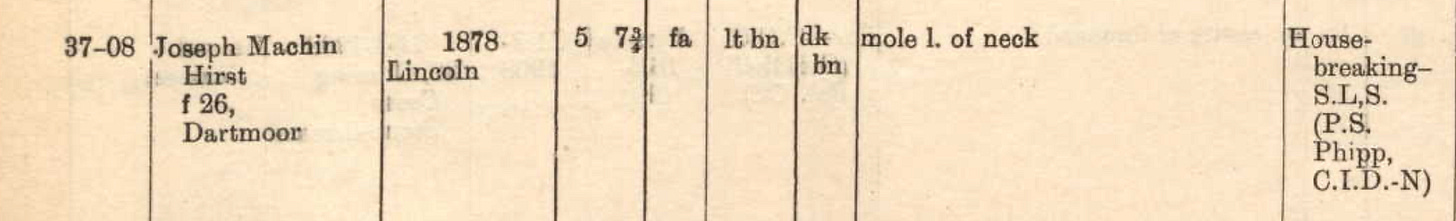

Joseph Machin was duly convicted of housebreaking, and sentenced to four years in prison. Criminal registers note that he was just under 5 feet 8 inches tall, with light brown hair and dark brown eyes.

On his release from Dartmoor Prison on 11 January 1908, his status recorded in the Habitual Criminals Register, Joseph stated that he intended to resume his career as a private detective in London. However, it’s not clear whether he actually did so, or whether that was just something he told the authorities: perhaps that is what he intended to do, only soon realised that he needed money quicker and that re-establishing himself as a private detective with a criminal record might be rather difficult.

Therefore, Joseph instead found work at a cement works in Cambridge - he claimed to be a chemist there. The 1911 census shows that he was still single, and boarded with widow Mary Bullen and her family. Mary had a daughter, Elizabeth Ann (known variously as Lizzie or Lily), who at the time was 28 years old. On the 1911 census, Mary stated that her daughter had been married three years, and that she had seen her only child die. Elizabeth’s married name was given as Dawson, but no record of a marriage between a Bullen and a Dawson can be found, and I have not been able to find a child’s birth either.

However, despite Elizabeth being listed as married, she and Joseph started an affair, and moved to the Gravesend area of Kent, where they had a son in 1914. Two years later, they married in Brentford, away from friends and neighbours, perhaps to avoid gossip.

However, they stayed living in Gravesend, where the 1939 register records Joseph as working as Chief Clerk to a cement manager. Therefore, his work in the cement industry would prove far longer-lasting than his job as a private detective, and there is no evidence that he committed any further crimes after his stint in prison. Joseph died in Kent in 1946, aged 68.

Image from the Habitual Criminals Register from The National Archives, via Ancestry. Illustration from Wikipedia (public domain).

Sergeant Fripp’s first name is not given in press reports, but it the references are likely to have been to Isaac Fripp, who joined the Met in 1884, aged 28. He worked as a constable in Y and N divisions before being promoted to sergeant in 1895 and spending the rest of his career in P division, Camberwell. Isaac retired from the police in 1909.