The private detective and the society suit

Edward Drew kept his head down as a private detective - unlike one couple, whose divorce made the headlines

Edward Drew ran his private inquiry office from 64 Victoria Street. You could contact him via telegram (using his telegraphic name 'Drutec' - Drew detective) or by phone, on Victoria 2497. He was a man of experience, having previously served in the Metropolitan Police for just short of 27 years, and reaching the heights of Chief Inspector in CID. But he was also the grandson of a police officer, giving him a long history of law enforcement.

Yet Drew's background was more diverse than it might sound to modern ears. His father, Timothy, was an Irish immigrant, who after being widowed in the early 1860s had worked as a labourer and a watchman. His wife, Yorkshire-woman Mary, had given birth to at least eight children before dying in her early 40s, all of them born in Bromley, east London. After she died, Timothy moved to West Ham.

Edward had initially worked as a labourer, like his father, but then joined the police at Vine Street on 21 November 1881, aged 22. His record shows a steady rise through the ranks, from PC to sergeant, then to inspector, and finally, two years before he retired, becoming chief inspector. Then, on 5 October 1908, he left the Met.

He settled in Hampstead with his wife Eleanor; they only married in 1904, Eleanor having previously been widowed. In their 40s when they wed, they had no children together, although Edward became stepfather to Eleanor's son - also called Edward - who was 11 when they married. Edward may have become a private detective as soon as he left the Met, supported by his police pension, but he is only listed as such in the two Post Office directories for 1910 and 1912, and the 1911 census.

In 1921, Edward and Eleanor were still living in Hampstead. Shortly afterwards, they moved to Sussex, where Edward died in 1927. Eleanor continued living in Brighton until her own death, 25 years after her husband, and having been widowed twice.

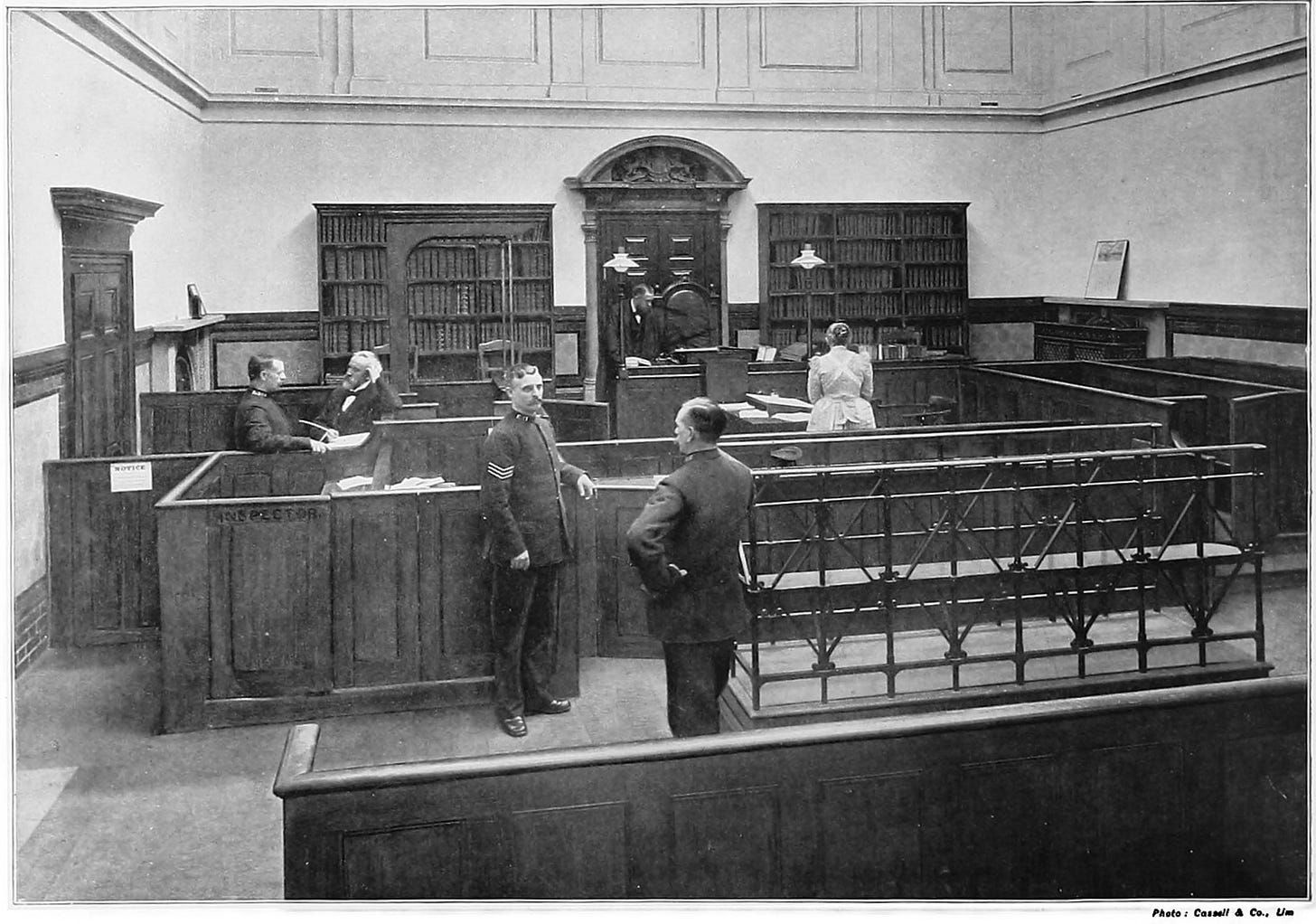

The Bow Street court in 1895

Those are the basics of Edward's life; as a private detective in London, he is less in evidence than some other, perhaps more publicity-hungry private eyes. There are no big adverts for his services; mentions of 64 Victoria Street are for other businesses that were also based there at the time. However, we do know that in April 1911, he was mentioned in a case at Bow Street magistrates' court, when Henry Fulcher accused James Duffield of Bristol with assaulting him. The assault had taken place during a meeting of Schweppes shareholders.

Fulcher was a pensioned police officer, who was now employed as a private detective - and his employer was Edward Drew. Fulcher had taken on work to act as private security at the shareholders' meeting; the company had had previous issues at such meetings, and wanted the men to prevent any breaches of the peace. During the meeting at the Hotel Metropole, one of the shareholders kept interrupting, and so Fulcher and his colleague John Henry had carried him out of the room. He proceeded to kick Fulcher on his thigh, and tried to throw an inkstand at him, until he was stopped by Henry. He was duly fined for the assault.

So Drew employed other detectives to take on work for him, not on the usual divorce watching in this case, but to act as 'heavies'. He was also able to draw on his contacts and friendships in the Met, to employ others who had retired from the force.

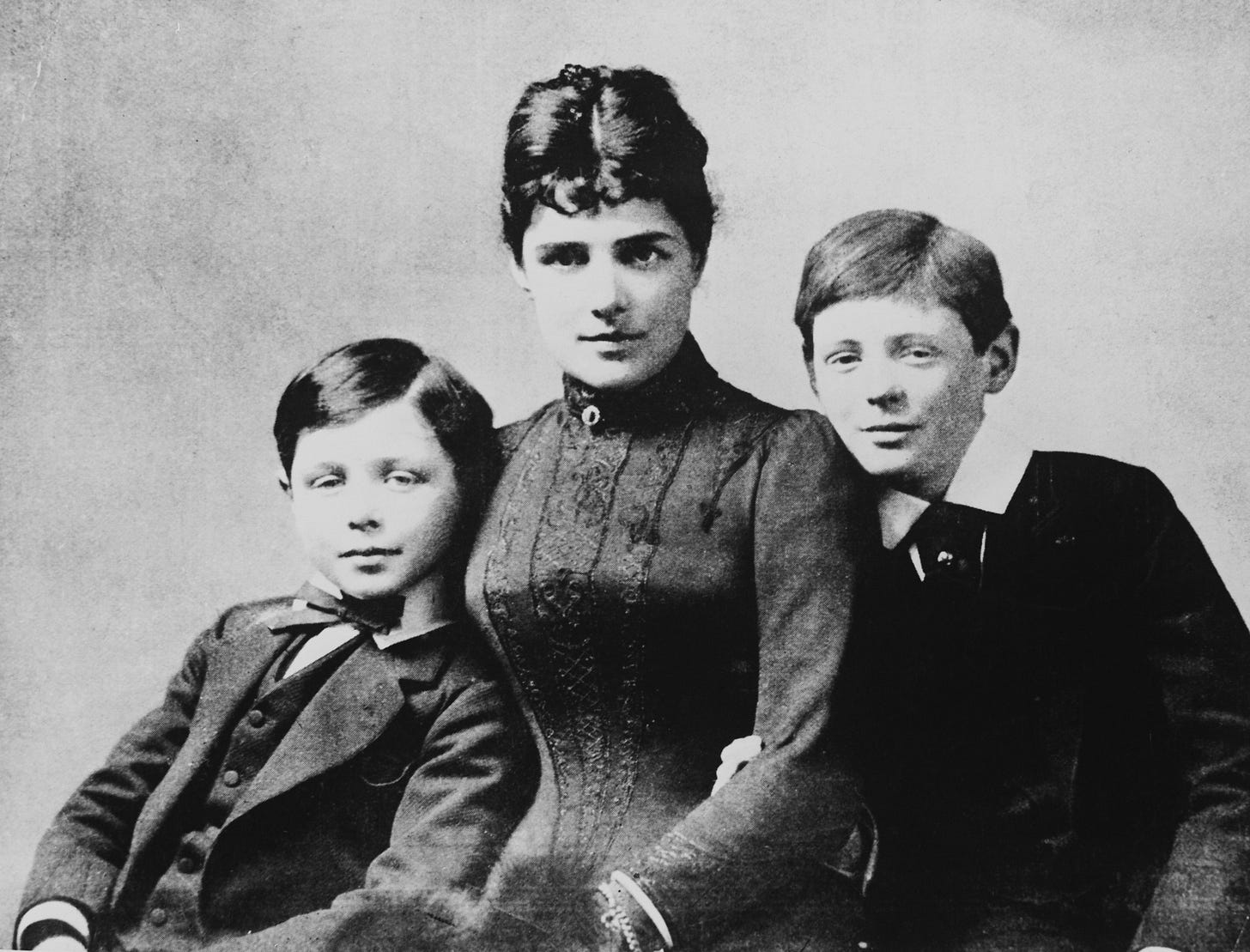

In the spring of 1913, Drew was still in business. At this point, he was involved in a divorce suit between American-born Mrs Jennie Cornwallis-West and her husband, George Frederick Myddleton Cornwallis-West. Jennie had petitioned on the ground of desertion and misconduct, the former based on her husband's non-compliance with a previous decree of restitution of conjugal rights.

The couple had been married in July 1900 at Knightsbridge, but on 23 December 1912, George had walked out of their house on Norfolk Street, off Park Lane, and never returned. Jennie had then petitioned for the restitution of her conjugal rights, with the decree being issued on 3 March 1913. Her solicitor, Everard Brown, had gone with Edward Drew to the office of Messrs Charles Russell & Co, where they served George Cornwallis-West with a copy of that decree.

Edward Drew had been commissioned to 'keep observations' on George, and made inquiries at the Great Western Hotel in Paddington, where a Captain and Mrs West had stayed there between 28 and 31 March. He then interviewed one of the hotel chambermaids, a Louisa Minton, showing her several photographs, one of which was of George. Louisa picked him out as the man who had stayed at the hotel with his 'wife' (this was the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell, born Beatrice Tanner, who he was having a long affair with, and would later marry).

Edward Drew gave evidence in the divorce case, being described as 'late chief detective-inspector at Scotland Yard', rather than as the more humble 'private detective'. His evidence was trusted, and Jennie Cornwallis-West was awarded her divorce. Jennie was famous for more than this divorce, however; having previously been married to Randolph Churchill, and thus Lady Randolph, she was also Winston Churchill's mother.