The Poison-Pen Case

In 1906, a sea captain needed a private detective's help in finding out who had been sending his wife threatening letters...

Mrs Caroline James lived in some comfort with her second husband, Captain Arthur Parkinson James of the Royal Navy. Their main residence was Hays Hall in Market Drayton, Shropshire, although they would soon relocate to Braydon Hall House in Minety, Wiltshire. Caroline had been a widow when she married Captain James in 1903. Her first husband, the wealthy Percival White Bushby, had died the previously year, aged 56, leaving his widow with a healthy amount of money which she could live off in some style.

In 1906, Caroline was enjoying life. She was busy - she had three daughters by her first husband, and a son by Captain James (the couple would have a daughter three years later). She enjoyed spending her money, too: she had recently bought herself a motor car, which she enjoyed taking her friends out in. Buying a car also necessitated a new wardrobe of special motoring clothes, and Caroline had duly bought herself some.

Image of the Hotel Metropole from Leonard Bentley/Flickr (cc)

On 20 May that year, she had needed to visit London, and so had booked a few nights at the Hotel Metropole on Northumberland Avenue. Whilst there, however, she was horrified to receive an anonymous letter, addressed to Mrs James at Hays Hall, which her servants had duly forwarded on to her. The letter writer knew a lot about her, her past, and her family, and aimed to shame her for trying to distance herself from her origins. It started:

"Now that you have taken up the position of not caring how your mother exists, I have decided to act in a way which will do you more harm than you can well imagine."

The letter writer told Caroline that her sisters Edith and Ada had been 'keeping', or looking after, their mother since Edith had left school. Edith had written to Caroline telling her that her brother Arthur had died and asking if she could pay for a headstone for him. Caroline had apparently ignored the letter, and ignored the fact that her mother was facing penury. The letter writer thought Caroline's treatment of her mother was 'abominable', and demanded that she start paying her maintenance of £1 a week 'to support your mother until her death'. Her mother's address was helpfully provided, and the date by which the first payment had to be made: 22 May. If she did not make the payments, 'public exposure' of Caroline's treatment of her family would start. The letter concluded,

"Every person, from lord to cottage, in your district, shall know all about you and yours...Take heed ere it be too late, for this is no idle threat."

What seemed to gall the letter writer most was that Caroline had £5,000 a year from her first husband, and he implied that in her desire to get money, she had married twice and then disowned her family for being poor and needy. When Caroline refused to pay the money to her mother, ignoring the letter, a series of 'scurrilous' postcards followed, stating that her mother was 'practically starving':

"What a blackguard you must be to allow this old lady to live in poverty while you go about in style on the late Mr Bushby's money!"

What the letter writer apparently didn't know is that Caroline had had a falling out with her mother over 20 years earlier, and that they had not talked since. She had not paid her mother any money to help keep her, nor had she helped her sisters with their costs - although she had been paying her sister Amy money, to help her as she was disabled.

But were Caroline's family members so poor? The letter writer stated that her mother, Louisa Burnand, was living in poverty in Dorset Gardens, Brighton. However, she had herself married a wealthy man - stockbroker Lewis Bransby Burnand - in north London in 1858. The couple had a lot of demands on their money, for they had at least 17 children, most of whom survived to adulthood. However, they were also able to live in comfort in Croydon, with several servants. Lewis had, sadly, died aged 49 in 1884, but his widow inherited his estate, and was looked after by her 12th and 13th children, Edith and Ada, who were a decade younger than Caroline, the fifth child and third daughter.

The children soon grew up; the girls started to marry, and at least one, John Lewis, emigrated to Canada. Eldest child Arthur Bransby Burnand became a musician and composer, adopting the professional name of Anton Strelezki. He appears to have been something of a fantasist and a problematic child, despite his professional success and talents. He appeared in court in 1893, charged with an offence under the Criminal Law Amendment Act; he also claimed to be the brother of Sir Francis Cowley Burnand, the editor of Punch. His brother John Lewis, conversely, said that Sir Francis was their uncle. Although he may have been a distant relative, he was an only child, and certainly neither their brother or uncle, and disliked their claims so much, he wrote to the papers asking for it to be published that he was not the relation they boasted he was.

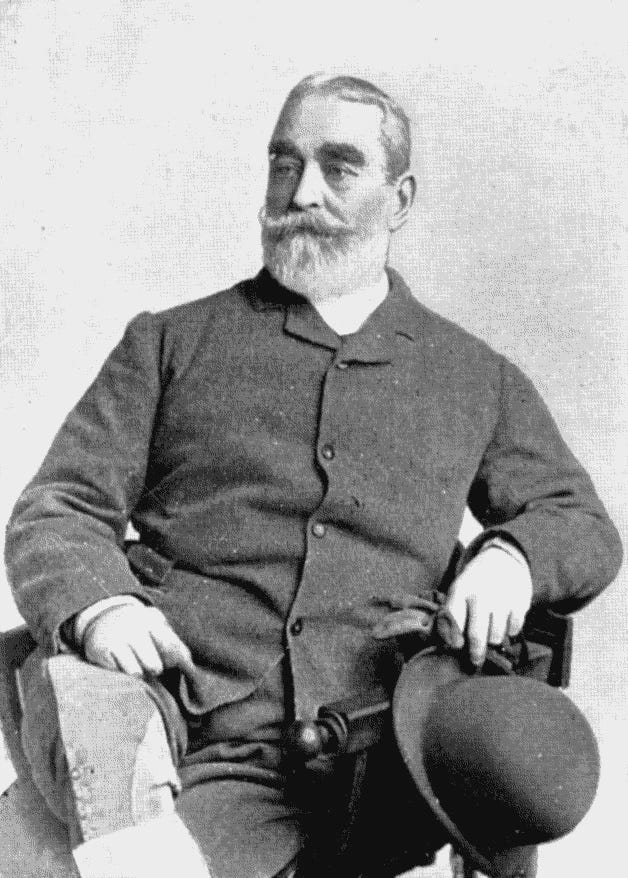

Sir FC Burnand - claimed by the ‘other’ Burnand family as their relative

Arthur Bransby Burnand died in early 1906, aged 47, and this seems to have prompted the letter writer to get in touch with Caroline. He had a detailed knowledge of how Caroline's grief-stricken mother was suddenly struggling financially, and how at least two of her daughters were having to devote their lives to looking after her. He wrote to Caroline telling her that he could not understand how, in a family of 16 (as it now was), the duty to support and clothe Louisa was falling solely on two of its members.

Caroline James was not amused by the letters. She told her husband about them, and he promptly got in touch with private detective John George Littlechild, the former Met police Chief Inspector. Captain James took the batch of letters and postcards to the detective's office off Regent Street, and asked him if he could investigate, hoping the letter writer could be identified. Littlechild duly undertook some research, noting where the letters had been sent from. Eventually, he homed in on an office in Bucklesbury, London, and made an appointment to meet with the man based there - a land agent and surveyor named Thomas Henry Church. To avoid suspicion, as he was well known, Littlechild used the pseudonym of George Langton when making his appointment.

Church appeared to have no links to the Burnand family, and was a well-educated, well-dressed man who appeared to have no need for money himself. But when Littlechild turned up for his interview with Church, he became convinced that he was, indeed, the letter writer. Littlechild reported his findings back to Captain James, and he reported the case to the police.

In August 1906, Caroline James drove herself to Bow Street Magistrates' Court in her car, which was full of her friends. She wore a smart white driving coat for the occasion. Thomas Church also dressed well for his court appearance, in a blue lounge suit with green tie, and was described by the waiting press as looking 'aristocratic' and 'well dressed'.

Bow Street Magistrates’ Court

In court, Caroline James was an impressive figure. She refused to be cowed by the occasion, refusing to answer several questions posed to her by Church's counsel, because she didn't think they were relevant, or because they were invasions of her privacy. She refused to say why she wouldn't talk to her mother, or how much money she had - and the magistrate agreed that she shouldn't have to answer such questions. All she would say is that she had 'very good reasons' as to why she had disowned her mother two decades earlier.

Church's defence appeared to be that although he had written the letters, they were not to extort money for himself, but simply to offer charity to Louisa Burnand. He claimed to be an old friend of the Burnand family, who had become 'exasperated' with their sudden dive in financial circumstances. He admitted he had not known that Caroline had a 'warranted' reason for not helping her mother. His counsel tried to argue that he shouldn't face a jury trial, but the magistrate disagreed, and decided he should go for trial at the Central Criminal Court.

When he appeared there, on 11 September 1906, no evidence was offered for him demanding money with menaces, and so he was found not guilty of that charge. He pleaded guilty to publishing a defamatory libel against Caroline, but he had apologised and promised never to repeat it, and so, after paying £50 and a friend paying another £100, he was released on these recognisances, a free man.

The only link I can find between the Burnands and Thomas Church is that in 1901, he and his family were living in a maisonette in East Grinstead, in the same county as the Burnands. But they were living in Brighton, and there is no evidence for how the two families knew each other; perhaps Thomas's wife was friends with one of the Burnand daughters, and heard them complain about all they had to do for their mother. After his Old Bailey appearance, Thomas Church returned to his work as a surveyor. Louisa Burnand moved back to London, where she died in 1913; and Caroline James returned to her comfortable life with her captain husband.

It was another positive story for John Littlechild and his detective agency; he had tracked down the poison pen letter, and Thomas Church's guilty plea meant that Littlechild would be associated with the successful conclusion to a criminal case.