The Notorious Public House Spy

William Gentle Huckle was a private detective who would do anything to stop people drinking or selling alcohol - even if it resulted in a libel case and a transatlantic flit

In the 1890s, one name would be synonymous with the zealotry of temperance campaigners, and always used in full: William Gentle Huckle. This one man made numerous appearances in the press from 1880 to 1900, and his desire to shame people for drinking would lead to not one but two cases of libel, absconding from justice, and a flit across the Atlantic. His personal life was equally colourful.

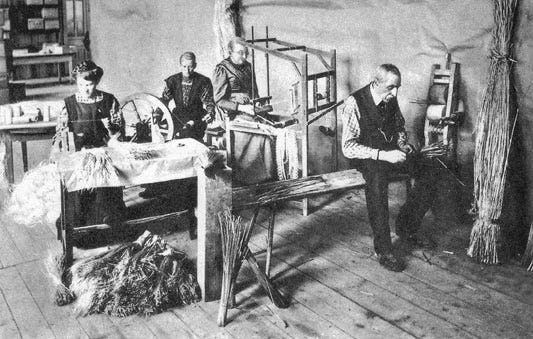

His origins were rather ordinary. He was born in Luton in 1860, to a family steeped in Bedfordshire's straw plaiting industry. His father, Thomas, was a straw plait manufacturer, working hard to maintain his large family. William's parents, Thomas and Ann, would have 14 children, of whom eight would die in infancy or childhood, and each of whom was given the middle name Gentle - Ann's maiden name. Each time one child died, they would name the next after them, and William was named after an earlier William Gentle Huckle, who died two years before his birth. Although mortality was higher in Victorian times, and childhood death was by no means unexpected, William would grow up in a house that was regularly seeing its young members die, and we can't imagine how that would have felt to the young boy.

The Huckle family worked in the straw plaiting industry

William initially followed his father Thomas into the straw plaiting trade, but he was already proving to have a tendency to make statements that made others raise an eyebrow. In 1879, at the age of 19, he first appeared in the local paper. He was writing letters to the Luton Reporter, which were rapidly criticised by others, who noted that in his case, a 'little knowledge is dangerous.' A year later, in 1880, he wrote some inflammatory comments to the Luton Times and Advertiser. Another reader also named WIlliam Huckle (the name being fairly common in Luton) quickly responded to the paper, 'emphatically denying' that he had made the comments, and concerned that readers might assume he was the letter writer, rather than the young straw worker.

As soon as he was 21, William married. His wife, Charlotte Agnes Booth, was five years his senior, a plumber's daughter who was born in north Oxfordshire but brought up in Buckinghamshire. In her teens, she had moved in with her older sister Julia and Julia's husband, the latter having relocated to Luton for work. Charlotte would live in Luton for the rest of her life.

Less than a year after their marriage, at 11.30pm on 30 March 1882, the Huckle home on Cumberland Street in Luton nearly burned down, when a fire broke out. It was Charlotte Huckle who was woken by the smell of fire. It was an early warning of the disruption that her husband frequently left in his wake.

She and William had three children, two of whom died in infancy, leaving just their son Frank Ernest to bring up. But Charlotte would bring Frank up largely alone. After 1881, William Gentle Huckle does not appear on any census living with his wife and son. Although he may have been absent initially due to work, at some point, they certainly separated, and would maintain separate households.

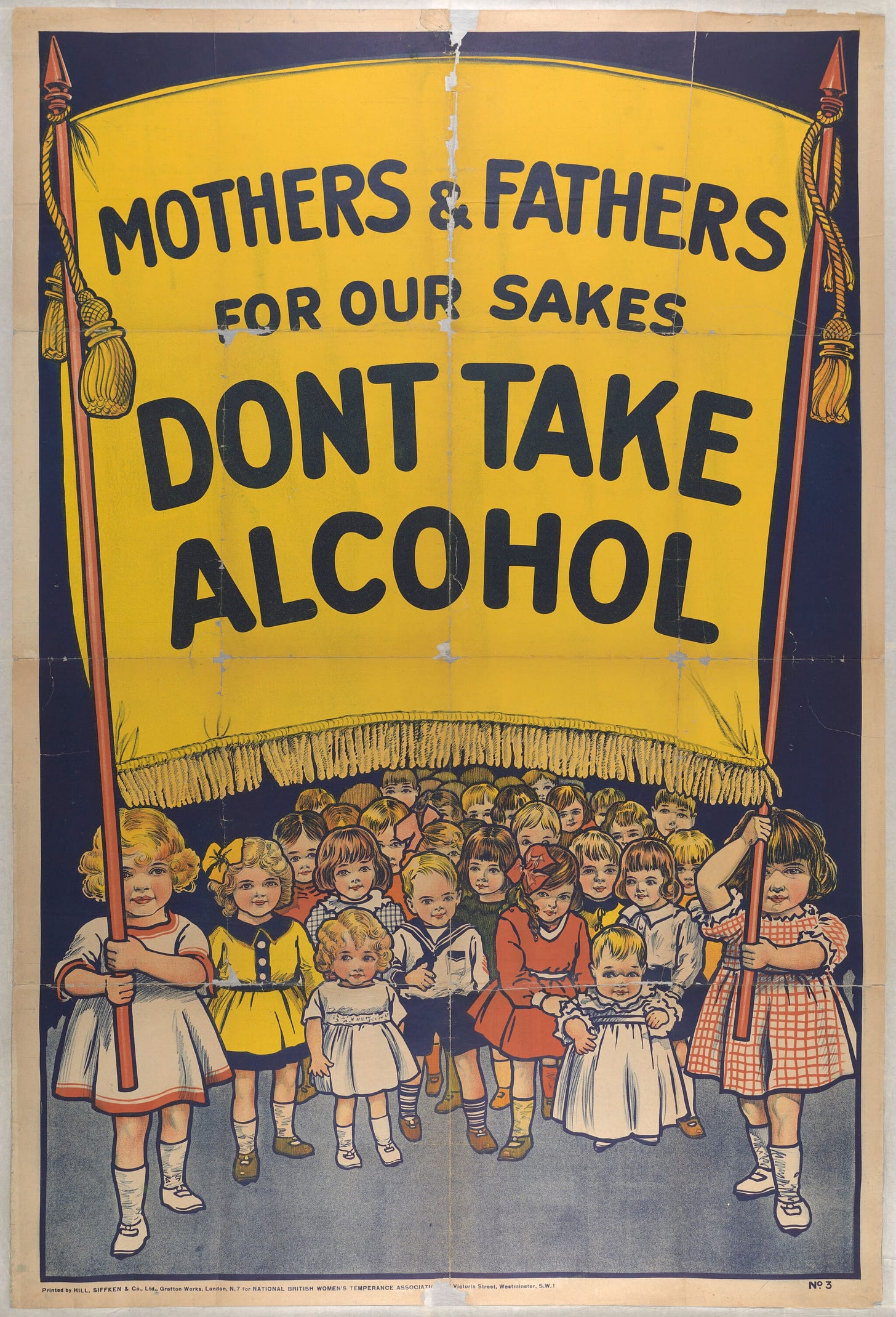

William Gentle Huckle left Luton and the straw trade, and set himself up as a private detective, working for the temperance movement. At one point, he claimed to have private detective offices at Exeter, Bristol, Warrington, Rochdale and Manchester. Each office was established under a different name, and he claimed to be the 'Chief Detective' of the United Kingdom Vigilance Committee. This committee worked to find evidence that would be used against pub landlords when they applied for renewals of their licences. In Exeter, where he was based on Jubilee Road, Huckle was also employed by the Temperance Party.

Huckle believed he was fighting on behalf of the temperance movement (image from Wellcome Collection)

Huckle monitored local pubs for evidence of illegal drinking. He also seems to have spied on individuals, acting as a kind of moral crusader. Known for his recording of information in a little notebook that went everywhere with him, he would peer through windows to try and spot people drinking. For some time, he was seen almost as a Robin Hood figure, his detective work being in a good cause, and was, if not quite respected, he was well known and seen as being a committed supporter of temperance. In Exeter, he became known as 'the Exeter vigilante detective', but was not universally liked; in 1894, he took a local engineer to court for assaulting him.

In his employment, William Gentle Huckle was determined to get results by whatever methods he could. He started to accuse various individuals of intemperate habits, reporting activities that were simply made up. When, in 1895, he became cross that Mary Ann Mather, a Manchester widow who ran the Albert Inn on Morton Street, was trying to find out more about him and his practices, he went too far in his quest for revenge on her.

In Manchester, Huckle had run his private detective office, on Upper Brook Street, under the name of WIlliam Baker. He was therefore charged as William G Huckle, alias Baker. He had been watching Mrs Mather's pub, and she soon became aware of this, getting increasingly anxious about him. She thought she would find out more, and so tried to call at his office, but he was not in. Huckle found out about the visit, and became annoyed, so he tried to extract a revenge.

He placed a placard offering a reward of £25 for anyone who could tell him who had broken into his premises and committed a burglary - at the time that Mrs Mather was known to have visited him. He then wrote a letter, as William Baker, stating that the person seen speaking to Constable Lloyd on the corner of Upper Brook Street and Grosvenor Street on 15 August was known to be 'in some way connected with the burglary'. Mary Ann Mather had been at a music shop there on the night in question, and had had a conversation with Constable Lloyd after she left the shop. Baker claimed he had asked the police constable to give him the name and address of the woman he had spoken to, but that Lloyd had refused.

Mary Ann Mather was quick to prosecute Huckle, and rightly so, as he had accused a respected member of the community of being a thief. However, he was determined to avoid facing justice. He was indicted to appear at the next Manchester Assizes, but given bail - and he promptly disappeared. A warrant was issued for his apprehension, but William had, seemingly, disappeared.

It took two years to track the private detective down, and it emerged that in order to avoid a conviction, he had fled across the Atlantic to New York. In November 1897, the New York police managed to track him down and arrest him, sending a telegraphic cable to Scotland Yard to let them know that the 'notorious William Gentle Huckle, known throughout the whole of Great Britain as the Public House Spy', had been caught. Detectives from Britain then travelled by ship to the US, where Huckle was handed over to them and brought back to England.

The news of Huckle's arrest after so long understandably made headlines across the English press, but the newspapers then went very quiet. Did Huckle face court? It seems difficult to believe that the press wouldn't have reported it if he had. Huckle is not obviously in the 1901 or 1911 censuses; in fact, although his wife Charlotte remained living in Luton and present in the archival record, her husband was significant for his absence.

The next thing known of him is when he started a relationship with a woman 20 years his senior in Sussex. Louisa Mann was from Devon, but may have moved to the Lewes area with her parents when they retired. She was from a wealthier background than Huckle's first wife. She and Huckle lived as man and wife, and had two daughters in Brighton - in 1916 and 1917 - before settling in south London. Huckle was no longer a private detective; by 1921, he and Louisa were working together as second hand furniture dealers. They could not marry, as Charlotte Huckle was still alive; in fact, even after she died, in 1926, they did not marry immediately. They only did so in 1931 when Huckle may have known he was in failing health - he died in the Camberwell area in 1932.

Huckle was, by all accounts, a committed member of the temperance movement, but he took the cause, and his work, too seriously. His quick temper meant that he disliked people investigating him - rather than the other way round - and he refused to take responsibility when things went wrong. He believed that the ends justified the means.

What happened to him immediately after his return to England, and up until the point where he popped up in Brighton, I don't know; but William Gentle Huckle was certainly a complex, and fascinating, individual.

This intrigued me as some of the places in Sussex are near to where I live. I did a couple of searches for him and found him with another family on the 1901 census in Southampton via FindMyPast. He is "Chief of International Detective Bureau". His wife is Alice and they have 3 children born in the US.