The men (and women) of Arrow's Detective Agency

One London detective agency's longevity was centred on its choice of employees, as a delve through the archives shows

I’ve spent a considerable amount of time researching 19th and 20th century private detectives, and one of the agencies that has come up time and time again in my research is Arrow’s.

Arrow's Detective Agency was established at Rolls Chambers, 89 Chancery Lane, in London, by two former police detectives. Charles Arrow was the man who gave his name to the agency, but he established it in partnership with his former colleague, Henry Derby.

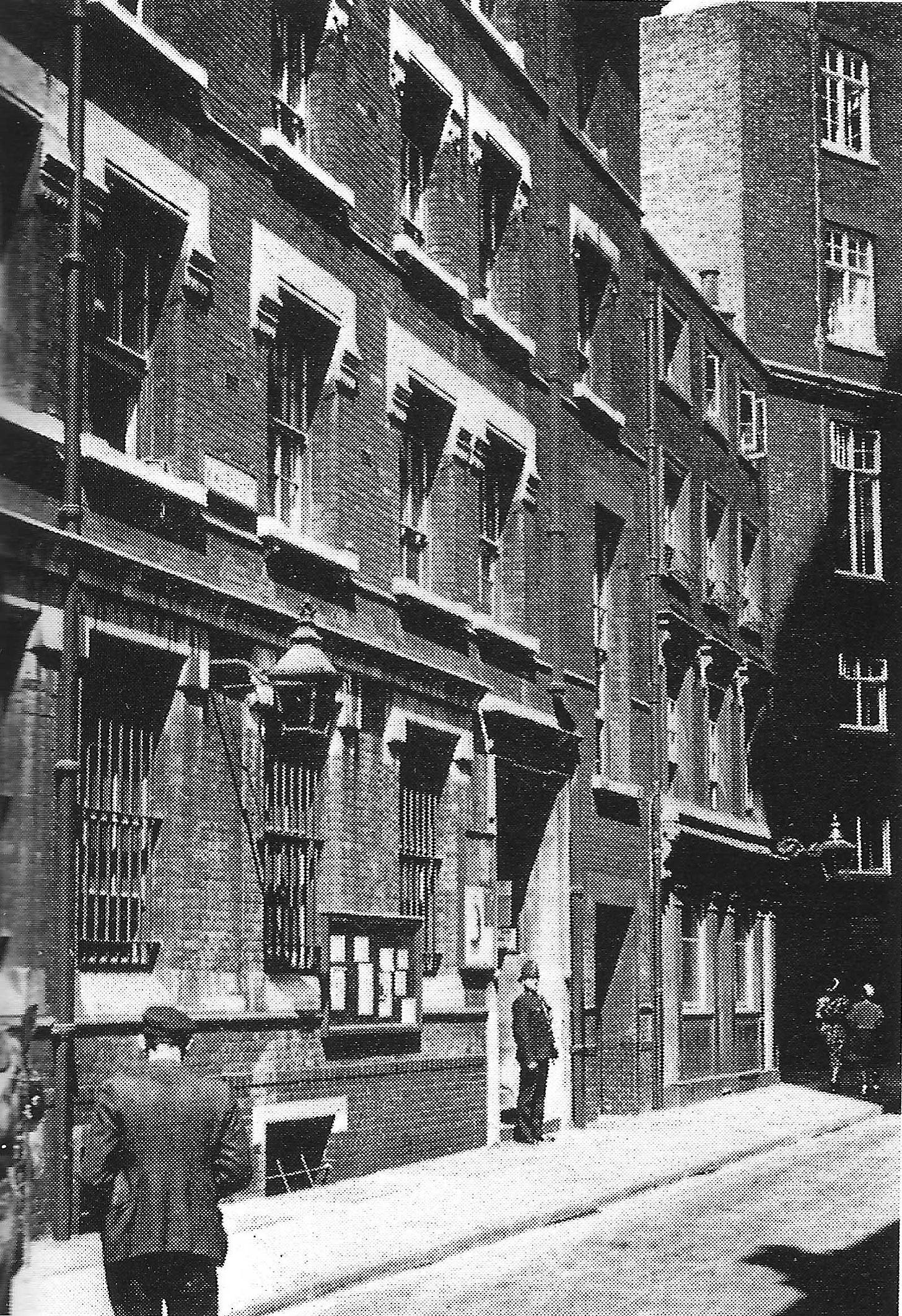

Arrow’s Detective Agency was based in this building on Chancery Lane, London (photo ©️Nell Darby)

Charles Arrow, who was from Stanwell in Middlesex, was born in 1861. At the age of 19, he joined the Metropolitan Police at Rochester Row, serving at Vine Street and Marylebone among other locations. He was in the police for 26 years, reaching the rank of Chief Inspector in CID before retiring in July 1907. When he left the Met, he stated that he intended to draw his pension from his home in Barcelona - Casa Ranzini - but this was no retirement, but simply a retirement from the Met. For a brief spell - only until 1908 - Arrow worked as defacto chief of the Spanish Criminal Investigation Department, before returning to London (for more about his Spanish career, and why it ended, see this article).

Henry Derby, meanwhile, was three years Arrow's junior, and was originally from Hertfordshire. He had joined the Met at Great Scotland Yard in December 1882, aged 18. Her retired in 1909, after 27 years' service. Like Arrow, he was a Chief Inspector by the time he retired, working in D Division. Both men, then, had been policemen since their teens, had been married, and were still only in their 40s when they retired. Although they had their police pensions, they were not ready to sit back and relax; Arrow, particularly, clearly found that the move to Spain was not quite what he thought it would be. They therefore decided to set up their own detective agency, utilising the investigative skills they had learned in the Metropolitan Police.

There were key differences between the pair, however. Henry Derby, the son of a publican, had been widowed in 1900, and had no children. In 1901, he had remarried (both his wives, confusingly, were called Annie). Charles Arrow had been married to his wife Alice for several years, with the couple having two sons, one of whom had died in infancy. He had briefly been an assistant schoolmaster before joining the police, and was the son of a coachman and a laundress. However, the two former police detectives were of a similar age, both living in west London. They got on well, both professionally and personally. Initially, the agency did well under its joint management, having plenty of work - helped by the owners' police contacts and experience. However, on 29 August 1913, a notice appeared in The London Gazette, stating that the partnership between Charles Arrow and Henry Derby had been dissolved the previous month, and that in future, the agency would be run solely by Charles.

What had happened? Why did the men decide to end their partnership? It could simply been because of Henry Derby's poor health, rather than any dispute. Henry died on 30 May 1914, only a year after his involvement in Arrow's Agency ended.

The agency, however, continued. It was mentioned in relation to various cases into the 1930s, and Charles Arrow ensured he utilised his prior experience in order to gain publicity for the agency. Throughout his detective agency career, from the Edwardian era until the mid 1930s, articles appeared in the press written by Charles, or interviews with him, in which his prior status as 'one of the original Big Five at Scotland Yard' given prominent placing. Cases that he had worked on were covered, and, perhaps inevitably, he produced a book about his experiences ('My Life as a Scotland Yard Detective'), in which he noted that he 'began thief-catching at an early age'.

Charles Arrow, a sketch based on contemporary press photographs ( ©️Nell Darby)

Most of the private detective agencies were run by men with a keen eye for publicity. It was a competitive arena, with many London-based agencies competing for custom. Selling stories to the papers - whether they be stories of successful cases or memoirs of their founders - was a way to get the public to associate detection with their agency name, so that if, in the future, they needed a job doing, they would remember who to ask. Arrow certainly did this with his press articles; his former status at Scotland Yard making him immediately noteworthy. However, the detectives he employed also saw their names in print.

One of these was John McIntosh McPherson who, by the 1930s, was a partner at Arrow's. Like Arrow, McPherson was a former Met man - a divisional detective inspector. He had joined the police at Vine Street in 1891, when he was 22 years old, and served over 28 years in the force. He had been injured twice in the line of duty, one his injuries being a stab wound to his left thigh. He had retired in 1918, and become a private detective.

The former Vine Street police station, where John McPherson started his career

In 1934, McPherson gave an interview with the Daily Mirror, where he noted that Arrow's 'occasionally employed women to act as detectives'. In fact, women had been employed as detectives for a long time, with there being female detectives at various agencies back in the 19th century. By the 1930s, Britain had a couple of famous 'lady detectives', such as Maud West and Kate Easton, so it's not clear why McPherson thought the employed of the odd woman was such a newsworthy thing to say. However, Arrow's certainly employed one lady detective for a period of several years. This was Mrs Schwab, who is mentioned in various news articles between 1922 and 1932, when she was said to have died. She was variously named as Kate, Katie and Ettie, but her real identity is not known, and there is no death registered in any permutation of these names for July 1932, when the newspapers reported her passing.

It is possible, though, to find out more about the agency's team of male detectives, and some of their other, backroom, staff. Women were more commonly employed by Arrow's as shorthand typists and clerks; in 1921, Ivy Davies was one of their typists. She was a 20-year-old Welsh woman who lived with her widowed mother and her sisters in Paddington. Her career ended with her marriage in 1928. One man who always described himself as a clerk was Englebert Ralph Thole, but newspapers referred to him as a private detective, so he either made his way up the career ladder, had more of an admin role at Arrow's, or preferred not to tell people what he actually did for a living - although some private detectives loved publicity, others felt that their job was seen as rather 'seedy' by others, and preferred to obfuscate. Whatever his role there was, Thole was working for Arrow's certainly from 1914 until 1920. He had custody of his two young daughters, and Arrow's provided him with a sufficient income to look after them - but only just, as he remained reliant on accommodation with his mother, and, later, his older sister.

Arrow's proudly boasted that it employed a former member of the Constantinople Intelligence Service as one of its detectives. This was Christopher John Searle, about whom little else is known - although he did work for Arrow's for at least eight years. Many detectives were employed on a freelance basis for agencies, calling at their offices each day in the hope of work, and only getting paid when they were taken on for a specific job. However, Arrow's had a team of detectives who had some longevity and loyalty. Searle's eight year employment and Mrs Schwab's decade appear not to have been unusual - and John McPherson was employed there for at least 20 years.

Other established members of Arrow's agency were drawn from the ranks of the police, like John McPherson. Police detectives were able to get their pensions after 20 years of service, and many did so. However, given that these men had often joined the police in their late teens or early 20s, they were still fairly young when they retired, and were not ready to sit back and relax yet. Private detection offered them the chance to utilise the skills they had learned in the police, giving them variety, an interesting job, and money to supplement their pensions. McPherson did this, as did James Moore, who had been a police sergeant before becoming a private detective in the first decade of the 20th century, at which point he was nearing 50 years old. By 1921, he was working for Arrow's, alongside William Tournor, who had been a constable in the Met before joining Arrow's at around the same age as James Moore.

Other detectives employed by Arrow's came not from the Metropolitan Police but from other agencies. Percival Henry Butler was one of these men. He was the third generation of his family working as a private detective - he had watched both his grandfather, Henry, and father, Reuben, working in the field. As soon as he was old enough, he joined Reuben, both men working for Messrs JG Littlechild and Co, an agency based at Great Marlborough Street in London. Littlechild's, as I’ve written about before, was run by John Littlechild, a former chief inspector at the Metropolitan Police. He died in 1923, and his agency also died with him; at this point, Percival Butler gained a job at Arrow's.

Arrow's continued to be one of London's leading detective agencies, busy with a range of cases well into the 1930s. Its success came to an end only when its founder, Charles Arrow, died in 1936. Its staff moved on to other agencies, and other jobs, but a study of its staff provides an insight into the type of men and women who worked in this industry, and where they had learned their detective skills.

A version of this article was previously published in the Discover Your Ancestors digital magazine. Many thanks to the editor for allowing me to republish here.