The Don of the Dud Detectives

Charles Brown's activities drew the ire of one periodical, which gave him a dubious nickname and instigated a years-long vendetta against him...

The Don of the Dud Detectives. This isn't my headline, but that of the popular Sunday periodical John Bull in 1913, when it ran a piece on the private detective Charles Brown, who, it emphasised, was a German.

It was not long before World War 1, and the thought of a German pretending to be British, and working in investigation, might be thought to be of interest to readers. Of course, not everything was as the paper recorded - the man in question was actually Viennese. More to the point was that his credentials as a private detective may not have been as they seemed, and this is what John Bull (owned by Liberal MP Horatio Bottomley) claimed to really object to.

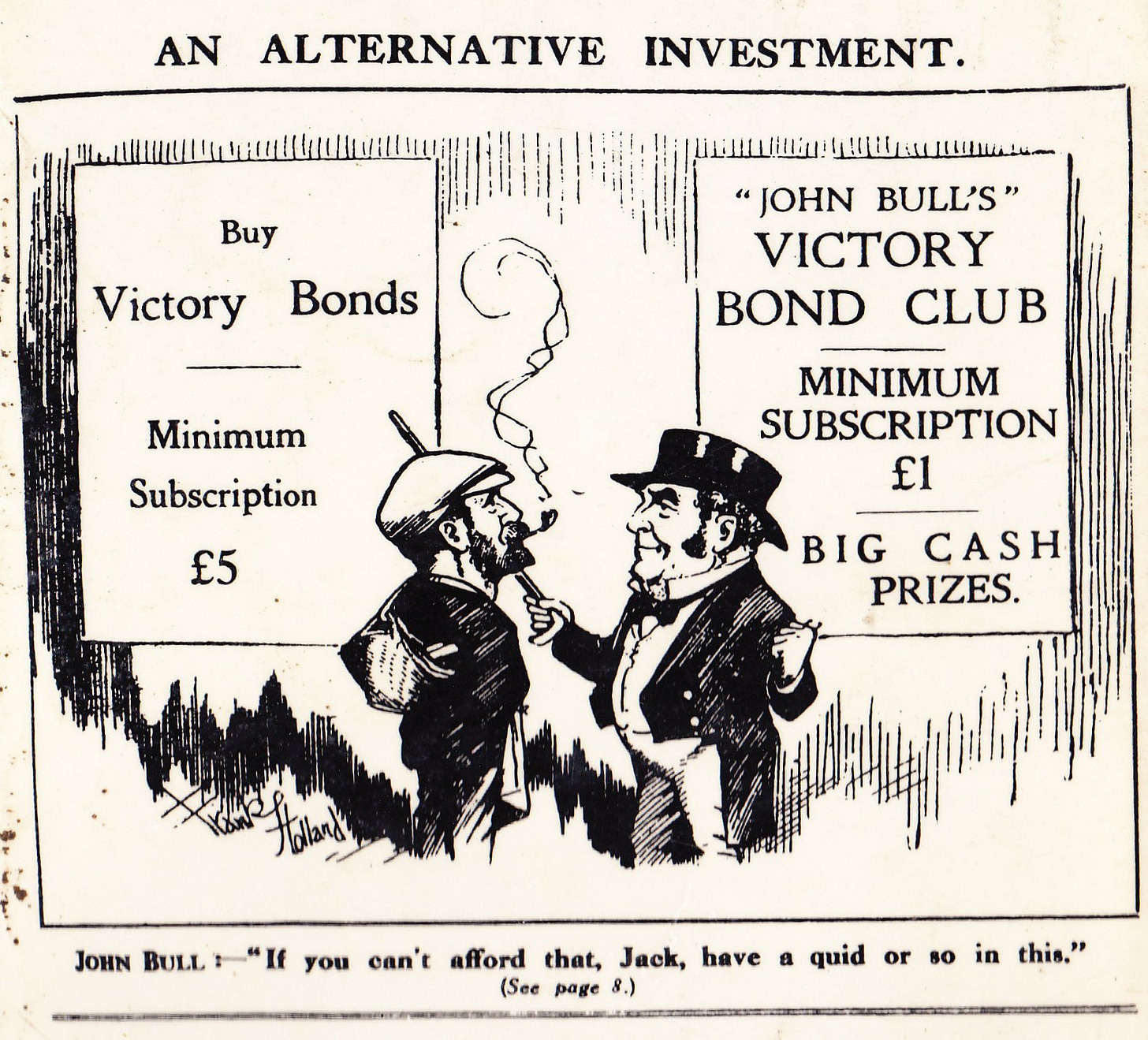

Horatio Bottomley used John Bull to promote an extreme anti-German sentiment during World War 1 - but also to run lotteries and prize draws. He was a bankrupt himself, but was scathing about others in similar situations.

Charles Brown was the founder of Brown's Private Detective and Enquiry Agency, based on New Oxford Street in central London. It had started advertising its services in 1913, but Brown had worked as a private detective before this, from his home in Maida Vale. However, in his Maida Vale life, Charles Brown was actually a man named Johann Burger.

Burger, born in Vienna in 1883, was in London by 1909, when he married a girl from Birmingham. He anglicised his name early on to John, and spent most of his career in the hotel trade - in 1911, he was working as a hotel waiter, and in 1913, a hotel porter. Private detection was something he originally did on the side - in August 1912, he advertised his services in the Ealing Gazette, giving his home - 12a Clarendon Terrace - as his work base. He offered free legal advice, help in divorce cases or unspecified 'trouble', watching individuals, and claimed to have references from 'leading London solicitors', which seems unlikely. He set out a charge of three shillings to make confidential inquiries.

He had one brief mention in the press in October 1912, when he was alleged to have sent out two young detectives to solicit and incite a postman to burgle a widow's home in Kelvedon, Essex, but the case was seen as a 'waste of time' and the two detectives were found not guilty.

One of Burger’s adverts, from The American Register of 22 February 1914 (via British Newspaper Archive)

By 1913, though, John Burger had become Charles Brown, and, with a journalist friend named Robert Rohm, he set up Brown's Private Detective and Enquiry Agency. The agency had office hours of 1pm until 4pm every day, and specialised in 'divorce, watching, tracing'.

In November 1913, John Bull called Charles Brown, aka 'the German Burger' (the newspaper's words) the 'Don of the Dud Detectives' - in a piece that described him and his industry as 'a menace to society'. John Bull was arguing that all private detectives should have to register with the Home Secretary to remove a scourge in London of 'these hangers-on of the legal profession' who were 'thieves and associates of thieves'.

The piece then investigated John Burger as a prime example of such a man, whose 'three shilling bait worked very well for a time'. Burger was criticised for fleecing the mother of a missing girl out of £50, without having found the girl. It was noted that because of such cases, he had had to moved from Maida Vale, change his name, and set up again at New Oxford Street. However, this wasn't the only issue with him. He had advertised in the German press as being able to give legal advice; and he had previously sued a septuagenarian widow for failing to pay him over £2. He lost that case, and the judge had said that 'although fraud had not been proved, the suspicion was reasonable.'

The Bow Street court, where Milner-Pugh was fined

Brown responded by instigating a libel case against the paper. In response, the paper decided to investigate his solicitor, George Milner-Pugh. It found out that Milner-Pugh (who had been born plain Pugh, but who had adopted the double barrelled name in the 1890s) was an undischarged bankrupt, and that in November 1913 - the same month it published its hit piece - the Law Society had 'decided not to grant him the renewal of the certificate entitling him to practice as a solicitor'. Despite this, he had continued to act for Brown. He had also lodged papers at Somerset House as solicitor for Brown's Private Detective and Enquiry Agency, and subsequently had to appear at Bow Street Police Court, where he was fined £1 4s and told that if he didn't pay within a week, he would be sent to prison.

John Bull had done a good job of presenting John Burger as a fraud and a shady character who fleeced women and had to change his name as a result. The stress on him being German was designed to make him look like a criminal foreign character, one who employed bankrupts and who falsely claimed to be able to offer legal advice. This was part of owner Horatio Bottomley’s longrunning and virulent campaign against any Briton with a German-sounding name. Brown was brave in trying to sue for libel, but he knew that his career depended on it.

The following year, in March 1914, John Bull published another long piece on 'Charles Brown'. It noted that he had now formed a Limited Liability Company, with capital of £1,000 divided into one pound shares. He had sold 13 shares to a newly arrived German immigrant named Köckler, who was promised employment as a private detective for 30 shillings a week. Brown anglicised Köckler's name to 'Richard Wilson' and created an official-looking police court document, complete with seal, suggesting that as a private detective he had powers to arrest individuals. The document was signed by the unfortunate George Milner-Pugh. John Bull obtained a copy of the document, and published it, complete with Charles Brown's large and extrovert signature. noting that neither Brown nor Milner-Pugh had the authority to produce it, and that the Divisional Court might be interested to see it. This piece was headlined:

A saucy Sherlock

A further hit piece was published in December 1914. This time, John Bull sounded slightly weary of having 'from time to time...published exposures of a man calling himself Brown'. It detailed how Brown had been trying to prevent it from publishing its exposés after issuing his writ for libel, and how he had subsequently tried to delay the libel hearing. Brown had frequently obstructed the newspaper's attempts to obtain a security in case of him losing the libel case - as a foreigner, he was deemed to have no goods in the country which could be seized to pay his costs. He falsely claimed that he had a three year tenancy on a house at Holland Park (which wasn't a tangible asset), and then that he had a tenancy agreement on 13 New Oxford Street.

Then the case got further delayed because Brown had been arrested and interned as an enemy alien (in fact, they alleged that he had been arrested as an 'unregistered Germany enemy, carrying weapons). John Bull had already paid a substantial amount to try and progress the case, but when Brown finally paid the paltry sum of £10 into court, having failed to follow up his action, the case was dismissed, leaving the newspaper pondering how to recover its expenses from the slippery private detective.

The staff of John Bull had long memories. Two years later, in 1916, the paper published another full column about Brown, describing him as a 'dangerous enemy'. He had been interned as an enemy alien, and had been carrying on a business that was 'of a highly suspicious character', and so John Bull was surprised to hear that he had 'contrived to regain his liberty'. It called for the Home Office to interrogate him, and recapped its dealings with Brown as evidence of his 'shadiness'. He had, additionally, posed 'successively, although never successfully' as an American, an Englishman, a Scotsman and an Irishman, in order to disguise his origins. John Bull wondered whether 'perhaps some patriotic Member of Parliament' could inquiry more into Brown's life and activities.

Against all odds, however, Charles Brown's agency appears to have limped on, but in 1918, it was finally dissolved. Brown returned to his former name of John Burger; his wife appears to have died, and in 1927, he married again. Finally, in 1939, as it became clear that a second world war was going to take place, he was finally naturalised. Johann Burger from Austria, alias John Burger, and now resident in Brentford, could no longer be described as a dangerous foreigner, having lived most of his life in the London area. He died in West London in 1964, aged 83.

Your writing is always so well researched and knowledge filled. Another piece I had to read, well tbh, I listened on my run. Brilliant