The detective who wanted others to know they were wrong

Glasgow-based detective Alfred Knowles used a different strategy to publicise his skillset

John Atkinson Grimshaw’s depiction of the Clyde, Glasgow, painted at the time when detective Alfred Knowles was living there

Last week, I looked at how private detectives used former successes - even if their link with them was more tenuous than they made out - as publicity in their newspaper adverts, sometimes using the same case for several years as an example of their skill.

This week, I'm looking at a Glasgow-based private detective who was keen to show that he was better than both police and press, by advertising how he had disproved a story through his own detective work.

Alfred Edward Knowles was a Londoner by birth, but together with his Essex-born wife, Mary, had ended up living in Glasgow. He claimed to have worked as a detective in the Glasgow Police ('recently of Central Detectives Department, Glasgow Police', as he stated in March 1880), although by 1886, he was obfuscating this by advertising in the London press that he was simply 'late of Detective Dept', thus implying that he had formerly been of the Metropolitan Police.

I have no evidence of him being in either police force, but certainly, by March 1880 until March 1883, he was working as a private detective with a base at 107 Dundas Street (likely to have been both a work and home address, as the 1881 census records him living there with Mary).

Knowles advertised in the Glasgow Evening Citizen and The Scotsman, but also in the English press when he felt the need to. His adverts usually took on the normal form - stressing his experience in the police, his 'personal' attention towards inquiries, and his abilities to trace missing people. However, in March 1883, he advertised in the Manchester press regarding a missing heiress. He had made his own inquiries, and felt that the whole story regarding this woman was not right. He stated in his advert,

'The girl for whom search is being made in Dublin is no heiress, but the daughter of a woman who left her years ago in Kingstown. This woman is now a domestic servant, near Glasgow, and is anxious to find her daughter. The story about the recovery of the girl and of the heiress is therefore incorrect.'

In this short but intriguing advert, Alfred Knowles highlighted his knowledge of Glasgow, his ability to find out information about an individual (he specialised in missing people cases), and his superiority to the other parties trying to track this woman down. The story about a missing heiress was intriguing, and would have caught the attention of readers, but Knowles then made clear that such cases were sometimes far more prosaic (from heiress to servant's daughter) and needed some local expertise to solve.

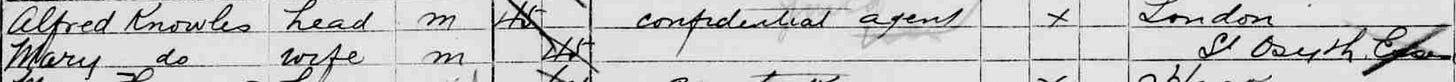

Alfred and Mary Knowles are listed in the 1891 census at Euston Road, London (TNA/TheGenealogist)

However, the Glasgow knowledge was not enough to keep Knowles in the city. By the start 1886, he had relocated back to London - the centre of the British private detective world - establishing himself at 79 Euston Road. His first advert there made clear that he was formerly of the Glasgow Detective Department, but within months he was omitting the city where he had worked.

He continued to work as a private detective in central London until at least 1891, but the 1901 and 1911 censuses show that he then changed career to work as an insurance agent. He moved out to south London before settling in Ardleigh, Essex, in his 60s, where he would spend the remainder of his long life, dying in his 90s.

Did Alfred’s strategy of publicising his skills by criticising others’ work? It seems to have been the only time he had done it, and one wonders whether it precipitated his move from Scotland to England. He may have been criticised for his approach, by those who were involved in this case - if it even existed. Or it could have been a strategy employed by someone who was struggling to make a long-term career in Glasgow and needed a new approach.

However, given Knowles’ relatively long spell in Glasgow, and his police experience, I suspect that he may have genuinely been frustrated by flaws in how he saw a particular case being investigated, and felt that people should know that it was not right.