The chequered life of Herbert Marshall

This Somerset-born private detective had a complex life, both personally and professionally

Over the next couple of weeks, I'm going to look at the exploits of one particular private detective - Herbert Marshall. Originally, I was planning to do a single synopsis of his life, but then I realised that he had a somewhat chequered history - both personally and professionally - that could not be done justice to in a single post. Today, I'll do a potted history of Herbert's personal life, and then I'll look at two cases he was involved in - one as a witness, the other as a defendant - in future weeks.

My drawing of Herbert (based on a contemporary newspaper illustration found at British Newspaper Archive)

I first came across Herbert when I was doing some stats on the 1911 census, and how many individuals gave their occupation as either 'private detective' or 'private inquiry agent' in that census. Herbert was one. But trying to work out his family was initially complicated: he had been married to a court dressmaker named Kate for 11 years, and had a daughter named Dorothy - but I could find no marriage for the couple, and no record of Dorothy being born to them. There were also various other people living with them, and from these, and with the aid of divorce records on Ancestry and newspaper accounts, I worked out Herbert's rather chequered personal life.

He was the black sheep of his family. His father, Henry James Marshall, was a clergyman, being a rector in various locations around England. Henry James Marshall had been born near Colombo, in what is now Sri Lanka, but he was living in London by 1844, when he married Lucy Maria Sadler. They were an educated and well to do couple.

At the time of Herbert Augustus Marshall's birth in 1863, the family was living in Clapton in Gordano, North Somerset, but they had previously lived in Derbyshire, before moving to the south-west. Herbert's older siblings were born in Belper, Westbury, Bristol, and Bath. Herbert was the second youngest of 16 siblings, only seven of whom were still alive by 1911. His surviving brothers grew up to be accountants and clerks; his sisters married well.

Herbert started his career traditionally enough, as a commercial clerk. The 1881 census records him visiting his older sister Augusta and her family in Somerset. The 1891 census states that he is now working as a secretary; he was recorded as single, and visiting a school in London. By 1901, he is a private detective and living with his wife Kate in London.

The problem with the census returns is that much of their information is not true. In 1891, Herbert was not single: in fact, he was married with a toddler. And the 1901 census isn't true either: although Herbert had a wife, she was not Kate Marshall.

In fact, back in 1886, Herbert had been staying on the Isle of Wight, and on 1 July that year, he married a woman named Emily Francombe Corbett in the island's register office. Emily had a sad past, and one that Herbert could have taken advantage of. A farmer's daughter from Yate, Gloucestershire, Emily's mother had died when she was six, and her father two years later. At the age of eight, she was orphaned.

Although she had older siblings, they were not old enough to look after her, and she was sent to an orphanage in Westminster. They trained her up for a life in service, and by the time she was 19, she was back in her native county, working as a maid at a Cirencester school. She then met Herbert Marshall, and married him: he gave his occupation on his marriage certificate as 'gentleman'.

In 1889, the couple had their only child, Dorothy Beatrice Lucy Marshall, and the couple lived in various residences in Fulham, St John's Wood and Putney. By 1896, however, the marriage had broken down, and they separated, with Herbert paying Emily £2 or £3 a week in maintenance - Dorothy lived with her mother. Marshall would later claim that he knew the marriage was over when the couple's five-year-old son, Brooks, died, and, on his deathbed, Emily told him that the child wasn't his.

By June 1897, Herbert had started to investigate his wife for 'immoral conduct'. He called on Emily at 11pm at night, and found her with one of his friends - a man named Charles Carey. He and Emily then argued, with Herbert telling her that he would not allow her bad conduct, and that if she continued her affair with Carey, he would take away Dorothy, and stop her maintenance. He returned the next day to get her decision on whether to stop the relationship, only to find that she had disappeared - the furniture had gone and the house was shut up.

Herbert was, at this time, apparently conducting work for the Canadian government, as well as for African ones. His business was booming. In August 1897, he had to travel to America, and was working there until the end of November. On his return, he contacted his solicitor - and it was apparently his solicitor's clerk, rather than the private detective, who eventually tracked Emily Marshall down to a house in South Twickenham. Herbert petitioned for a divorce in 1899, on the grounds of his wife's adultery, and he was granted a decree nisi, as well as gaining custody of nine-year-old Dorothy.

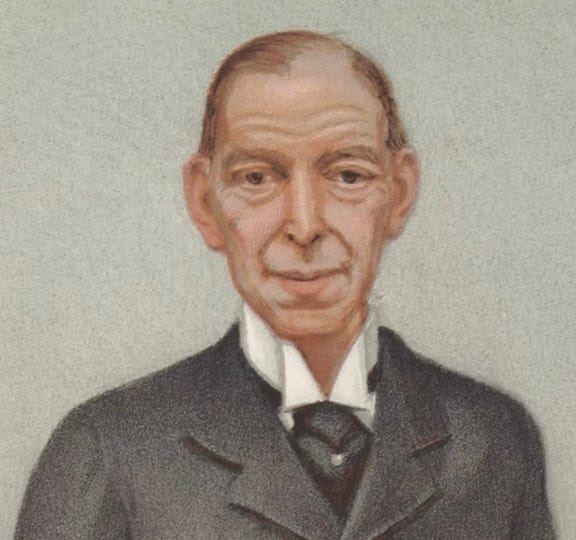

The Queen’s Proctor, Hamilton Cuffe, 5th Earl of Desart

So far so good. Only before the final decree could be issued, the Queen's Proctor - a senior government lawyer - intervened. Further evidence - presumably from Emily's side - had been submitted, which showed that Herbert had not been completely honest during the divorce proceedings. Emily may have been having an affair - but so too had her husband. Throughout 1899, Herbert had been having assignations with a Mrs Williamson in various houses and hotels in both London and Devon. His conduct was such, said the Queen's Proctor (who at this time was Hamilton Cuffe, 5th Earl of Desart), that he was refusing to issue the final decree. This meant that Herbert and Emily remained legally married.*

In around 1894, Herbert had established his own detective business. In 1900, he formed a limited company; he would have 500 shares, with the capital of £1000 being put up by a 'great friend' of his named Hanmar. In 1903, he was offered a job with the established private detective (and former Scotland Yard detective inspector) John Sweeney, and decided he wanted to accept. He therefore put his own company into voluntary liquidation, with no debts, in order to go into partnership with Sweeney. The new company, Sweeney & Marshall, started in January 1904, operating from 5 Regent Street in London, and saw a good influx of clients.

Kate Ker-Lane’s shop in Kensington. She lived with Marshall as his wife for many years

Life seemed good. Herbert was involved in a thriving private detective agency, based in central London, and now had a good home life too. However, the woman Herbert was living with - who he claimed was his wife - was neither Emily nor Mrs Williamson. She was Kate Rowles, a woman better known as court dressmaker Kate Ker-Lane. Kate ran a dress shop in Kensington known as Madame Kate Ker-Lane's Court Dress Emporium. In 1911, the couple had Alice Sinclair (nee Rowles) and her son Thomas Marshall Sinclair staying with them: Thomas would later be the executor of 'Madame Kate Ker-Lane''s estate.

Herbert could not marry Kate, because he was already legally married. Yet they had been living together since 1900. What had he told Kate? In 1905, he appeared at the Old Bailey as witness in a trial that brought his whole reputation into disrepute. He would claim that he did not know whether Emily was alive or dead, and that his private detection skills had failed when he tried to make inquiries into her: "inquiries which I made at the time failed to trace her." As I will show next week, what happened next dramatically exposed what had happened to her.

* Emily remained with Charles Carey, and appears in both the 1901 and 1911 censuses as 'Emily Carey', living with her 'husband' Charles.

Interesting - and great drawing!

Goodness, what a story! Great read, thanks.