Kimptonism - or the art of blackmail

It was their telegraphic address, but for Kimpton's Detective Agency, it could also be used as shorthand to describe their criminal activities...

Part of a series of Kimpton’s adverts in the Daily Telegraph of 31 January 1911 (via the British Newspaper Archive)

For less than two years, and just before World War 1, one of central London's detective agencies was Kimpton's. Based at 71 Strand, it placed numerous adverts in single issues of the London press, advertising its various skills, from finding evidence for divorce to locating missing people. It had two telephone lines, and its telegram address was 'Kimptonism'. Unfortunately, in 1912, it emerged that Kimptonism was also a very good word to describe how Kimpton's got some of its money: through blackmail.

Kimpton's was not, despite its name, run by anyone called Mr Kimpton. It was actually owned by Francis Henry Page, who appointed William Henry Glendinning as manager, and Frederick Marshall as clerk. Prior to setting up, Page had been a furniture salesman, and Glendinning a commercial traveller. Both were Londoners born and bred; both were middle aged men seeking more interesting, lucrative work with which to maintain their wives and numerous children.

Page had a chequered history, which included a conviction for obtaining money by false pretences in 1906. Glendinning, who had previously had a reputation for honest work, joined his new business at the start of 1911, but may have come to regret it. Their downfall came when they came into contact with an elderly countess.

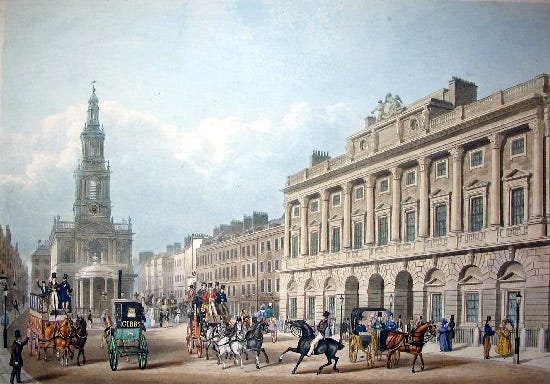

An earlier view of the Strand, where Kimpton’s agency was based

The Countess Anna de Hamil de Manin was a widow in her late 60s, her husband having been a French count. She was vulnerable to the approaches of men claiming to be in love with her, and had some sort of acquaintance with two in particular: a Daniel O'Connor and another man, referred to as 'Mr Dobby'. Whatever relationship they had had petered out, but the Countess later wrote a series of letters to the relatives of a Mrs Williams, who had since got engaged to Dobby. These - by what you can tell in vague accounts of the case - exposed the Countess's relationship with Dobby. The letters were written in 1907, and reached Dobby's hands; he sat on them until 1911, when he took them to Kimpton's Detective Agency.

It seems that both Dobby and the agency wanted money, and so Page and Glendinning started a blackmail scheme. They wrote to the Countess, promising to return her letters if she would admit in writing to having written them in the first place. Terrified, she signed a document they produced for her. But the men did not return her letters, and instead threatened her, ordering her to pay them £1,000 or they would fabricate a libel charge against her and make her spend a night in Bow Street's police cells. They threatened the poor woman for two hours at their office, until she was in a state of collapse, at which point they reduced the amount they wanted to £400. The exhausted woman signed four bills for £100 each, and handed over the jewellery she was wearing - a gold and pearl chain pendant - for 'security'.

Once out of the office, the Countess started proceedings against the agency, and Page, Glendinning, and their clerk Frederick Marshall, were all duly arrested and charged. They were tried at the Old Bailey, and the two main men were convicted and sentenced to 12 months' hard labour, to date from 9 January 1912. Frederick Marshall, who appears to have had mental health problems, was seen as having had a more minor role in the blackmail attempt than his bosses, and was released on his own recognisances of £100, and another bond of £100 from a Mrs Griffiths - presumably a friend or relation.

This was the end of Kimpton's Detective Agency, and of Kimptonism - it had been a shortlived venture. In the 1911 census, both Page and Glendinning had proudly recorded their occupations as private detectives. They would now need new occupations: Page became a cabinet draughtsman, whereas Glendinning may have become a journalist and PR man - reflecting his skill in creating adverts for his detective agency. I don't think Kimpton's was always a front for blackmail; it is more likely that it was a bona fide agency but one where its owner and manager got a little bit too greedy, saw a way to make some easy money - but found that the case of the Countess was one they would not win.

This is incredible and, as ever, so detailed and well researched.