Gentleman James and the Singer Sewing Machine heiress

Some private detectives were asked to act as their clients' bodyguards; for one man, however, this resulted in a protracted court case

Known in the Met for his shiny silk hat and matching umbrella, James Stockley was regarded as one of the force's most handsome and mild-mannered detectives. He had not one but two nicknames as a police detective: Gentleman James to his friends, and The Toff to those he arrested. Every day for 25 years, he would turn up to work in his silk hat and smart mourning coat to solve crime and catch criminals.

When he retired in March 1911, he turned his hand to private detection. Initially, as I've mentioned before, he established an agency with his old Met colleague John Walsh, before Walsh stepped down and their detective agency continued under the sole direction of Stockley. Over the past two weeks, I've looked at two of his employees - Albert Ansell and Charles Adams - but Stockley employed a whole raft of detectives, all based at his office at 8 John Street, Adelphi.

Stockley was born in St Pancras in 1863. His father, also named James, was a prison officer. Brought up in Islington and Finchley, young James married Agnes Harris in 1889, and the couple settled in Islington with their children, Dorothy, Ada, Arthur and Sheila (four more children - Ernest, Howard, an earlier Arthur and Marguerite - all died before their fifth birthdays). In the Met, James worked his way up from police constable to chief inspector at Scotland Yard, and in 1888, was involved in the search for Jack the Ripper.

By 1921, the Stockleys had moved out of central London to Isleworth, and then, in the 1930s, James Stockley, now in his seventies, retired and moved to Tiverton, Devon. At this point, after a long marriage, he and his wife Agnes also seemed to separate. Looking at their entries in various directories, this separation appears to have occurred between 1930 and 1934, with James moving to Devon whilst Agnes moved to Leeds.

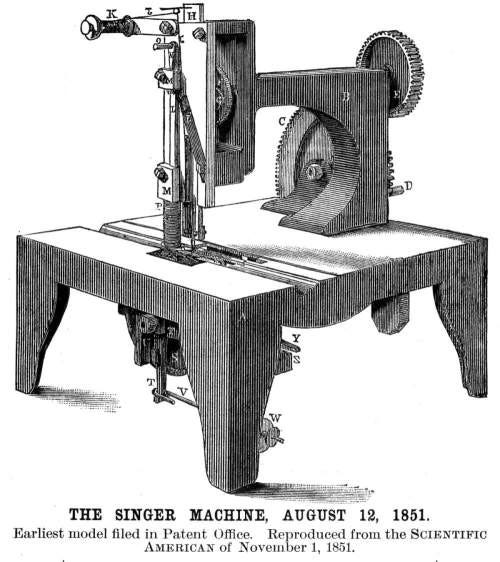

Although James had had two long and successful careers, as police detective and then private detective agency boss, these were almost overshadowed in 1934 by a rather newsworthy case. This may also have prompted the schism between James and Agnes Stockley. Two years earlier, Mrs Florence Adelaide Pratt, a 74-year-old American woman, had died in London. Mrs Pratt's rather ordinary name hid the fact that she was heiress to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune - her father, Isaac Singer, had founded the company in 1851. She was also regarded by a London mental specialist, who had regularly attended to her, as "eccentric, unstable and unbalanced."

Isaac Singer, Mrs Pratt’s father

Mrs Pratt, who had been widowed in 1924 when her lawyer husband, Harry, had died, left a will in which the main beneficiary was none other than Gentleman James. Her doctor, Alexander Malcolm Simpson, stated that her "main preoccupation seemed to be sex". She had become obsessed with Stockley, talking about him as though she was a "schoolgirl telling about her sweetheart. She said she adored him". She was, the doctor believed, madly in love with Stockley.

But how had she met the detective? Apparently, she had employed him as her personal bodyguard. It was not unique for a private detective to take on bodyguarding duties, but here, Mrs Pratt did not maintain boundaries with her bodyguard, and, being with him a lot and forging a friendship, she believed that she had fallen in love with the married detective.

After her death, there was, unsurprisingly, consternation amongst Mrs Pratt's family. Her sister-in-law, Margaret Alexander, had contested the will's validity on the ground that Florence Pratt was not of sound mind when she drafted the will. The case was heard in 1934 at the Surrogate's Court in New York; then, in 1935, the Supreme Court in New York unanimously upheld the will - in which Mrs Pratt had set out how her million dollar estate should be dealt with. Although James Stockley was the main beneficiary, with Mrs Pratt leaving him £5,000 a year for life, Mrs Pratt's chauffeur, Leonard Kay, also received a bequest. Mrs Alexander appealed to the Supreme Court, but although a newspaper report in 1943 stated that this will had been found to be invalid, other sources state that this was not the case, and that Stockley received his inheritance.

Mrs Pratt’s fortune was a result of the Singer sewing machine - although her husband had also inherited a multi-million dollar estate through his own father

Mrs Pratt was said to have behaved 'properly' until 1918. Then she became increasingly eccentric. It was stated that she had made six different wills in six years, and that she regularly became obsessed with various men, signifying her affections by giving them wads of banknotes or expensive jewellery. When her affections waned, she would then sometimes engage lawyers to try to get the money and jewels back. She moved to London to investigate the underworld, making friends with criminals, and learning how to commit crime from them. However, these criminals then started to threaten her, and so she engaged Stockley to protect her from them. Although she had then named him as her main beneficiary, she tended to change her mind frequently about who she wanted to inherit her estate, choosing random relatives' names, then made-up names, then the names of shop assistants she had bought corsets and other items from.

What James Stockley made of all this is not known. There is no evidence that he cultivated Mrs Pratt's feelings for him in the hope that he would inherit from her; it is more likely that he was unaware of what she intended, or, if she had mentioned it, did not take it seriously. But her decision to name him in her will caused an infamous court case in the US, and may have caused his marriage to rupture as a result. It also altered his obituaries. When he died in March 1954, he was commemorated as a man who took part in the hunt to find Jack the Ripper... but also as a man who had worked for an eccentric American millionairess. When his wife had died in 1948, she had left effects of £468. When James died only six years later, his were worth nearly £30,000. This amount of money was, in itself, newsworthy. The 91-year-old’s obituaries were, as a result, marred by the link between his personal wealth and the court case over an heiress' fortune.

John Creasey wrote a long series of books about a guy named "The Toff", but I doubt Gentleman James inspired his use of the name.