'A professional Sherlock Holmes'

From child custody to family annihilation, records show that Birmingham detective Edwin Bullivant was involved in a variety of sometimes shocking cases

Edwin Bullivant was described in one court case as a ‘sort of professional Sherlock Holmes’.

The term, in this case, was used pejoratively

For many private detectives, the only reference to them in the press is in relation to divorce cases - the bread and butter of their jobs. However, in the case of Birmingham detective Edwin Bullivant (also misrecorded as Edgar and Edward), we can get a fuller picture of the variety of work he was engaged in - not only divorces, but custody battles, arranging police honey traps, and even giving evidence in a horrific family annihilation case. Therefore, forgive me for a slightly longer post today, in order to detail this one man’s work.

Bullivant was born and bred in Aston, now an inner city suburb of Birmingham. Born in early 1877, he was the third of five children born to music professor and piano teacher George Bullivant, and his wife Elizabeth, who were both natives of Wolverhampton. He started life as a merchant's clerk, before becoming a railway inspector. In 1901, he was boarding with a local family - the Bakers, who comprised of commercial traveller Thomas, his wife Emma, and their two children. When Thomas died, the boarder, Edwin, duly married his widow, and the couple settled at Frederick Road in Aston - the road where Edwin had lived with his own parents.

By 1906, Edwin had established himself as a private detective, with an office on Corporation Street in the city centre. He operated for at least six years, and with some degree of success, given that he employed an assistant as well as a few freelance detectives when he needed extra help. It may also have been something of a family occupation; Edwin’s brother, Arthur, is listed in the 1911 census as a commercial clerk, but four years later, there are references to an Arthur Bullivant, private detective, in Birmingham, suggesting that the two siblings worked in the same field.

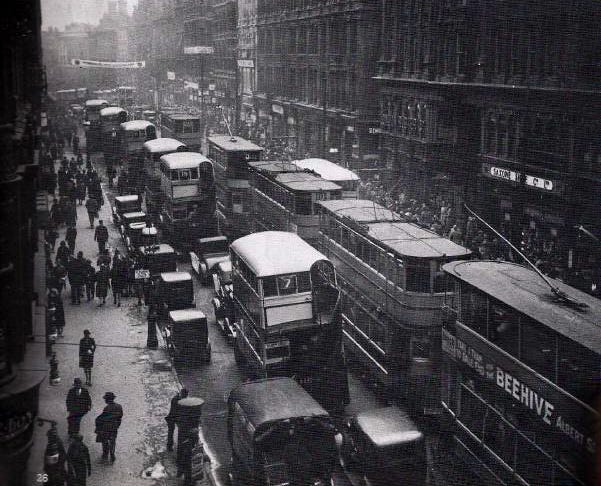

Birmingham’s Corporation Street - location of Edwin Bullivant’s office

In 1906, in the earlier part of his detective career, Edwin was commissioned by a local woman to investigate her husband. Emily Constance Barber, aged 31, was living in Sparkhill, Birmingham, with her husband James and their two young children, Edgar and Winifred. Although she had been married since 1897, Emily had long been suspicious, thinking that James was being unfaithful. She had therefore asked Edgar Bullivant to watch him. Edgar did so on around eight occasions, but found no sign that James was anything other than a loyal husband.

He met with Emily several times to reassure her, but soon realised how jealous a nature she had. The first time they met, she told Edgar that “knowing the life he [James] is living, I feel I could kill him.” The following week, she called on Edwin, and said, “If I can prove my suspicions, I shall kill him, the children and myself.” Edgar, shocked, responded, “But why the children?” Emily replied that she could not leave them behind. Edgar’s job ended when he failed to find any evidence against James; the Barber family duly relocated to Oxford’s Cowley Road, and that should have been the end of things.

However, three years later, in 1909, Emily suddenly killed her husband James, then Winifred, who was by then 10 years old, and then tried to kill 11-year-old Edgar Barber. Edgar put up a desperate fight, but eventually, Emily succeeded in killing him too. Finally, she cut her own throat. Edgar must have been horrified to find out that Emily had carried out her earlier threats, and shocked to find himself called as a witness at the subsequent coroner’s inquest, where it was decided that Emily was ‘unjustly jealous’ of her husband, and that she had murdered her family and committed suicide in a fit of temporary insanity.

Just a month after appearing before the Oxford coroner and his jury, Edgar was in court again, this time giving evidence in a more usual case – a divorce. Percival Frank Jones was also a jealous individual, but this time, he was jealous of his wife Elsie’s acquaintance with a naval officer, Mr Rogers. By the time of the divorce hearing, Mr Rogers was dead, having died of tuberculosis over a decade earlier. However, Percival was still jealous, even though Elsie had only met Rogers while on holiday in Cannes with her mother, and the latter insisted Elsie had never been alone with him.

Unfortunately for Percival, Edgar Bullivant had been employed by Elsie to watch him, and the private detective gave evidence that he had seen Percival Jones with one Bertha Reed – and their baby. Bertha was a typist in Percival’s company, and the couple had started an affair, leading to Percival having a second family in Ealing. On hearing Bullivan’t sevidence, he admitted misconduct, and the couple were given a divorce (Percival then married Bertha, and the couple soon had a second child).

Other referecens to Bullivant’s work in the press are also to do with divorces; in June 1911, he was employed to watch Annie Eliza Ansell, wife of the manager of the Crown Hotel in Snow Hill, Birmingham. He duly saw Annie with one Ted Mayfield, and saw that they were, in effect, living together. He served the couple with papers for the divorce, and Ted responded, “Well, I don’t suppose it will mean more than a life sentence for me.” After George Ansell, Annie’s husband, instigated the divorce petition, Annie got a job at the Enfield Cycle Works in Redditch, and continued to live with Ted, although she insisted that he was just a lodger. She was not believed, and the Ansells divorced – although it doesn’t look as though Annie’s relationship with Ted survived; instead, Annie married another man in 1916.

A more unusual case for Edwin came in October 1911, when he was implicated in the setting of a trap to catch a man named William Daw, a 26-year-old Birmingham tailor. Bullivant seems to have been employed by the police to pretend to be a police constable, and to persuade Daw to ‘do a bit of “watching” work for him’. In other words, Bullivant got Daw to agree to be a police spy, being employed to watch a public house for illegal activity. Unfortunately, Daw chose instead to try and defraud the chair of the Holt Brewery Company through blackmail (threatening to expose him for being involved with illegal betting at the pub). Daw was duly arrested and charged with fraud. In court, he insisted that he believed he was being employed by the police, and had merely followed their instructions. Bullivant was exposed as the ‘big, burly-built man’ who had posed as one PC Wilson to trap Daw into a crime, and Daw was duly found not guilty and discharged.

Another case involved the custody of a young child. Edgar was commissioned by the mother of an illegitimate child to remove the child from her uncle’s custody and to give her back to her mother. Cecilia Comfort Stannard was the mother in question; after giving birth to her daughter, Julia Haynes, in 1904, she had moved to South Africa, leaving the child with Cecilia’s brother – a caterer named Ernest Haynes. Seven years later, Cecilia returned – this time with the two children she had had in South Africa, after marrying - issuing a writ to her brother to return the daughter to her. Ernest, who had looked after Julia all her life, and regarded her as his de facto daughter, refused. Therefore, Cecilia engaged Edgar to help.

He called on an assistant, William Roberts, to accost Haines while he was taking his niece to play in a local park. What happened next was debated, but it ended up with the private detectives in court charged with assaulting Haynes. He argued that they had ‘pounced’ on him, hurting him and wrestling the child from him before putting her, visibly upset, into a waiting taxi that contained her mother. In court, Edgar was described as ‘a sort of professional Sherlock Holmes’ and he and Roberts as ‘nothing but hired bullies’. Cecilia was criticised in court for employing ‘thugs’ when she could have gone through the courts to claim her daughter back.

Edgar insisted he had refused to take on the case until he had proof that Cecilia’s child ‘belonged to her’ and that it was Roberts who had tried to hit him. However, both he and William Roberts were found guilty of assault, and fined (Edgar was fined twice the amount of Roberts, as he was. In charge). Julia remained with her uncle, and was still living with him in Birmingham ten years later.

Edwin Bullivant in the 1911 census for Frederick Road, Aston, with his wife and stepchildren

Finally, in a 1912 case, Bullivant employed Frederick George Marshall to take on a case for him. He was asked to watch a man named Joseph Astley – a spinner who, two years earlier, had been the victim of a work accident when his eye was injurerd by a piece of steel. He had received a compensation payment as a result, but now, the Central Insurance Company believed he was not ‘totally incapacitated’ and wanted his compensation to be reduced. They had duly asked Bullivant to help watch Astley, to find evidence that his sight was not unduly impaired; Marshall occasionally worked for Bullivant, and so he was asked to take on this role.

These cases, which were covered in the press over a three year period, give an insight into the cases worked on by this one Birmingham private detective, as well as showing how the more successful detectives took on temporary staff to help out when they were busy. The cases show that although a detective’s work might centre around divorce cases, every so often, other types of case were offered, with some blurring the line between legal activities and criminal ones. Other apparently simple cases of watching individuals could have longer term repercussions, with comments made by individuals having deeper meaning later on. The case of the Barber family annihilation was a case in point, and one that must have stayed with Edgar Bullivant for some time.

This piece really gives an insight to the private detective work undertaken at this time in history. It really is a fascinating insight.