A good deal of unpleasantness

Sheffield's Charles Keeling may have been a good private detective, but he was not a good neighbour

Some men and women were only private detectives for a relatively short part of their lives, and if you look simply at the evidence of their cases, or their families, you might only get a glimpse at what they were like. A detective with plenty of cases, and successes, who had a stable family with wife and children? You might assume that they were nice, law-abiding individuals. Sometimes, however, you need to look at other aspects of their lives, and their former jobs, to get a more realistic picture of who they were.

A case in point is Charles Keeling. In the late 1890s, and up to around 1902, Keeling was a private detective with an office at Figtree Lane in the centre of Sheffield. The road still exists, and although one side is unrecognisable from the 19th century, if you look at the other side of this narrow passage, it's easy to image Keeling at work here. Charles combined his work as a private detective with that of an accountant, but prior to this, he had worked as a solicitor's clerk.

In doing so, he had managed to transcend the class origins of his family. He was born in the Derbyshire market town of Wirksworth in late 1846. His father, after whom he was named, was a labourer in the local stone quarries, and he was the second youngest in a large family. His siblings, from the age of 12, were working, primarily in the cotton factories of the region as spinners and frame workers. Charles was the only son - or perhaps only surviving son - and by the age of 14, he was a solicitor's clerk. Although I don't know anything about his earliest work, by the early 1870s, he was working for a solicitor named Mr Gee, who may have been George Gee, a long-established solicitor in Chesterfield, between Wirksworth and Sheffield. Charles continued to work for Gee after moving to Sheffield with his first wife Ann, who he had married back in Derbyshire in 1866, when he was just 17 years old.

The Keelings moved from Derbyshire to Sheffield, where Charles set up his detective office

The Keelings lived in Talbot Place - number 14, the Keelings' first home, being a small mid terrace in dark Yorkshire stone. Many of the residents of Talbot Place moved properties regularly, and by 1879, the Keelings were at number 28 Talbot Place - living there were Charles, wife Annie, and daughters Annie and Mary, who in 1879 were 12 and 10 years old respectively. Charles had a respectable job as a law clerk, and a keen interest in the law and his rights. However, he also seems to have been both cocky and argumentative. In March 1879, he decided to prosecute two of his neighbours, claiming they had assaulted him. The men he accused were Arthur Platts, a 28-yearold scissor grinder, and John Best, 27, a file grinder. Arthur lived with his parents at 39 Talbot Place, having moved there from number 20; John Best lived at number 22 (he would later move to Arthur's old house at 22 Talbot Place).

These men, and their families, were neighbours in the small street, but they did not get along. They were members of the Methodist chapel on Talbot Road, but there apparently existed 'a good deal of unpleasantness between them'. Keeling had previously been bound over to keep the peace following an earlier incident, and now he claimed that Platt and Best were taking advantage of that to goad and assault him. He claimed that at 10pm on 18 February, he had left his house and was walking down a passage a few doors down when the other two men, without provocation, pushed him, tore his coat, and then started to kick him after he had fallen to the ground.

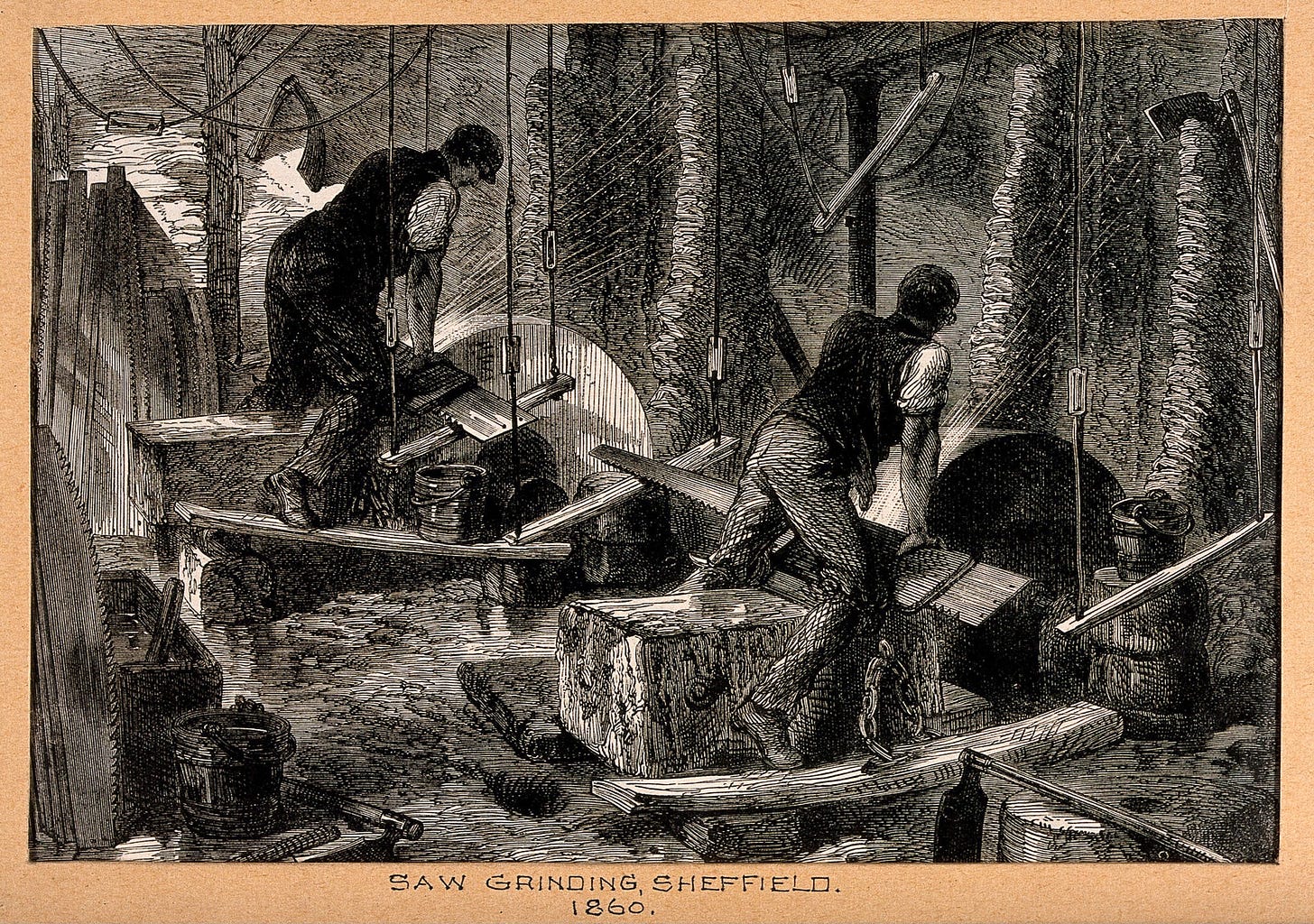

Grinders at work in 19th century Sheffield. Both Platt and Best worked as grinders (public domain image via Wellcome Collection)

Things were not quite as they seemed, though. The attack actually followed Keeling banging on Platts' window, scaring his mother Emily; he had also been telling others stories about Platts, to the extent that Platt had actually written to him, asking him to 'allay your animosity'. The court heard that Keeling had 'been seeking an opportunity of annoying' Platts, as well as his parents, when they were anxiously trying to avoid him and his temper. Luckily, there were witnesses who testified as to what had been happening, and how Keeling had actually hit Platts, causing him to bleed from his mouth and ear. Although it was Keeling who had brought the case to court as the plaintiff, it was he who was fined forty shillings for assault and again bound over to keep the peace.

Shortly afterwards, the Keelings moved out of Talbot Place to Mount Pleasant Road; Charles moved jobs to work as managing clerk to solicitor Edmund Knowles Binns. He was now accused of unprofessional practices in an 1881 court case, where he apparently had given an old acquaintance, commission agent Joseph Oates, who was accused of perjury, advice on how to get a 'very light' sentence. He was duly called into court to explain himself, and his testimony again suggests a stubborn man who was not willing to admit when he was wrong, and who had little respect for the courts.

One thing Charles had learned, though, was how interesting others' legal cases could be; he had previously, in 1872, given evidence in a bigamy case, providing documents to prove that an individual had indeed married while his first wife was still alive. Such cases involved detective work, finding the legal documents and evidence to make or break a case. Although much was going on in his personal life - his wife, Ann, died in 1887 aged 47, and he remarried the following year to widow Hannah Mason - he also sought change in his work life. He duly set up as an accountant and private detective, calling his business The Private Detective and Inquiry Agency, and, later, simply Keeling's.

His adverts in the Sheffield press combine facts with fiction: he claimed to be the only detective agency in Sheffield when there were certainly other detectives operating at this time, such as George Harrington. It was not a question of semantics about calling himself an agency as opposed to being a sole operator, for he still appeared to be working on his own, rather than with staff. He also claimed to be the oldest established detective office in Sheffield, although he claimed this only a year after opening the said office.

PRIVATE DETECTIVES - KEELING’S is the Oldest Established Office in Sheffield of thoroughly-trained, competent and intelligent Male and Females. Retired Police Officers, Male and Female Bicyclists available at an hour’s notice. Personal superintendence given. Private inquiries made with great caution and absolute secrecy - 9 Figtree Lane.

(Press advert, 1898)

The adverts certainly seem to have worked. In 1902, by now well established as a detective, Keeling placed an advert in the Derbyshire press to highlight that the 'enquiry agent referred to in case Parsons v Parsons', which had been reported elsewhere in that day's paper, was in fact himself. He added, helpfully, his work address, in case others wanted to contact him off the back of this case. But what was Parsons v Parsons? It was a divorce case between Hannah Parsons, of Brampton, Chesterfield, and her husband Henry. Hannah charged that her husband had deserted her, but she had actually suspected that he was having an affair with a 'young woman' named Hannah Smith. The affair had started in 1890 and was resumed, after a break, in 1893. Mrs Parsons tasked one of her sons, John, with spying on his father, but when Henry found out, he became angry with his wife, and 'took her by the throat and threatened to "do for her".' They continued to live together, though, until 1898, when Henry Parsons left home, and vanished.

Hannah duly commissioned Charles Keeling to find her errant husband. He duly did, finding Henry Parsons living with young Hannah Smith - they had now been together for ten years on and off, and had had three children, one of whom had died. Charles Keeling's evidence got Hannah Parsons her divorce, and custody of her four children by Henry.

At the same time as this case was progressing through the Divorce Court, Keeling was dealing with another one closer to home. He had won a court case against local farmer Joshua Mottram, and now Mottram owed Keeling over two pounds, plus costs. Mottram had failed to pay, and now he asked for Mottram to be committed for contempt. Mottram insisted he had not understood the resulting summons, but he was not believed; he was duly fined £5 and 'higher' costs.

Charles Keeling appears to have died in Sheffield in 1907, aged 63. He had the right personality to be a successful private detective - he was bloody minded, he had a good knowledge of the law, and he wasn't scared of a fight, whether physical or metaphorical. Was he a nice man to know? Perhaps if you stayed on the right side of him. But the experience of other Talbot Place residents, and other locals, shows that he could also be a man out for revenge, who could hold a grudge, and who didn't give much credence to the exhortation to love thy neighbours.